Hacking American Altruism for Foreign Missions - Lessons for the LCMS

When global mercy outpaces local faith, even the most generous church risks hollowing out its altars.

Live or travel outside the United States, and it quickly becomes apparent how uniquely altruistic Americans are. Most Americans are blissfully unaware that their generosity, kindness, charity, and volunteerism are globally anomalous. They assume everyone gives away a similar portion of their disposable income and time in the service of others. Their Anglo cousins come closest, confirming that charity is a cultural rather than a system artifact, but even they lag far behind.

Paired with this generosity is another cultural quirk - though a shrinking one -the assumption that most people and institutions can be trusted at face value. Together, this trait of unbounded charity and wholesome naïvete is a formidable moral force and an enormous economic engine for good. Unfortunately, they also make Americans easy marks for anyone who learns how to play the system—especially foreigners and foreign missions adept at “extracting loot” with a well-crafted marketing pitch.

The result is that fundraisers have shaped American donor psychology to instinctively favor visible mercy overseas over dreary maintenance of ministry at home.

The Arithmetic of American Generosity

The scale of giving is staggering. Measured as a share of gross national income, the United States far outpaces all peers1. Only the United Kingdom comes remotely close on absolute terms, contributing about $6 billion a year compared with America’s roughly $49 billion. In both percentage and absolute terms, no one else is even in the same league.

This flood of private philanthropy has made American donors the world’s default patrons of evangelism, humanitarianism, and activism alike—often without much idea of what they’re actually funding, because it’s all poured into the amorphous “do good, do better” bucket.

Fundraising Catnip

Mission fundraisers will tell you that extracting money for a foreign mission is far easier than for a domestic one. The same pattern holds across denominations as well as the secular sphere, which also depends on American generosity. Without U.S. private giving, many global NGOs would simply close up shop, as seen when entire networks shuttered after USAID funds were cut.

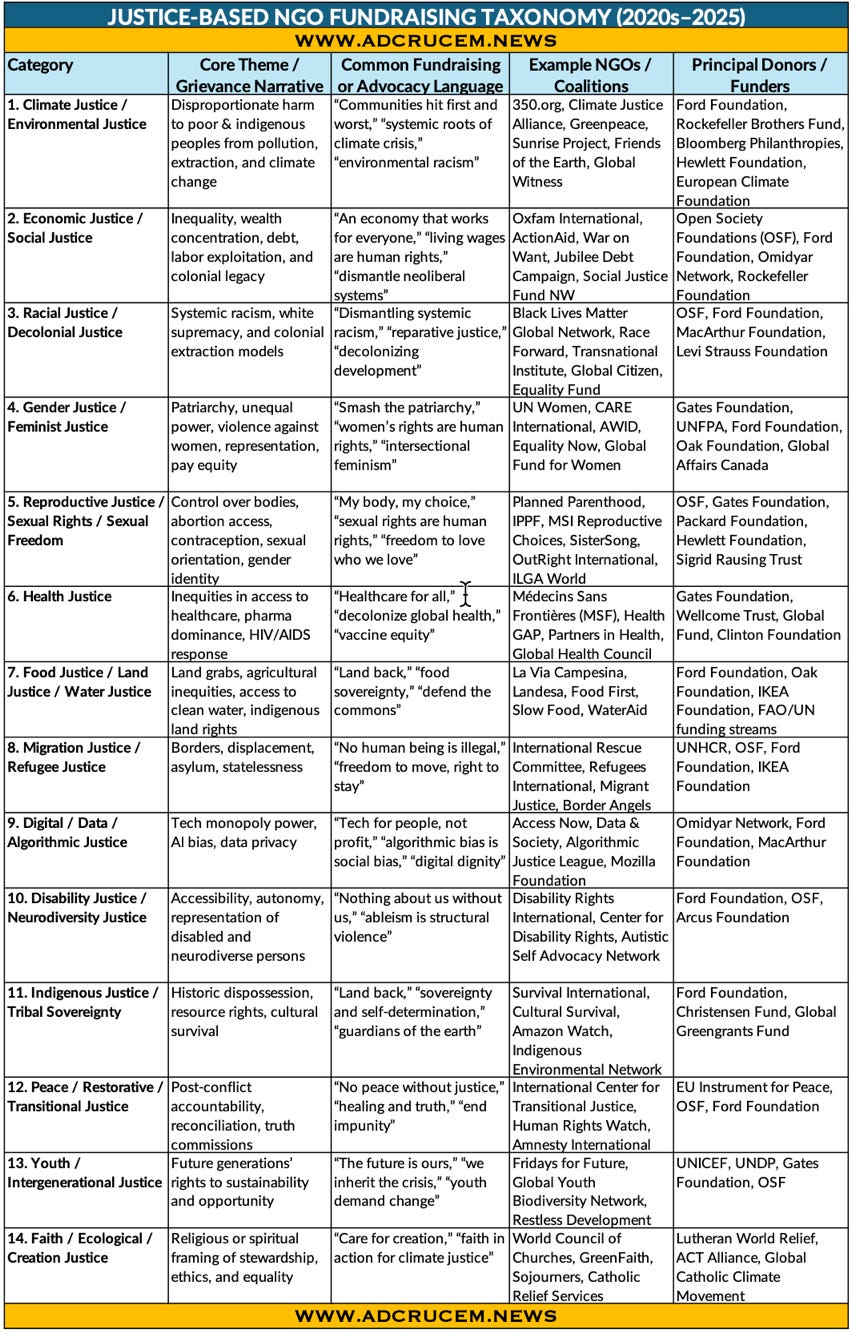

The secular “religions” of our age have mastered the art of fundraising through a new moral vocabulary—the sprawling family of global justices appended to human rights since World War II. They promise atonement through activism and salvation through grievances: climate justice, gender justice, racial justice, refugee justice and their many siblings. Their moral universalism claims to supersede Holy Scripture itself; the King of Kings is just another cool example of a selfless refugee. And unlike churches, the justice NGOs deliver their gospel of the new salvation and better mercy with American MBA learned industrial scale.

A global missionary enterprise cannot survive the domestic implosion of its host.

The New Bureaucratic Church

These organizations are not merely competitors to the church—they are its unheralded successors. Many are formally or informally tied to governments, multilateral agencies, and transnational faith networks. Their legitimacy is reinforced by how precisely they map their programs to the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (SDGs).

In practice, NGOs have become the administrative departments of the SDGs, executing the agenda of global governance while displacing or co-opting traditional Christian missions. Their gospel is this-worldly: redemption by justice, equity, and sustainable development.

This success is having a corrosive side effect. Confronted by the efficiency and funding power of secular NGOs, many Christian missions have begun to translate their theology into secular development language—framing discipleship as “capacity-building,” mercy as “sustainability,” and evangelism as “community empowerment.” The result is a quiet but devastating theological rupture: orthodoxy expressed in the queer idiom of the United Nations. It echoes the way karma has become the world’s most familiar and least examined religious concept: universally cited, rarely understood, and detached from its origins.

The Cosmopolitan Capture

At the top of this global ecosystem sits a cosmopolitan elite that moves easily among transnational corporations, global NGOs, diplomatic ministries, and international missions. They share education, vocabulary, and worldview. The risk is not merely bureaucratic creep but cultural capture: when the emissaries of one nation—or one faith—begin serving the interests of another, or worse, nothing beyond the amorphous gods of the new justices.

Unfortunately, there are several examples of this in the foreign entities the LCMS props up, including Germany’s SELK synod. Likewise, there are innumerable public and private horror stories about how the LCMS has been duped out of money abroad or cannot extricate itself from wayward bodies it is supposedly in fellowship with.

Every foreign service is vulnerable to nativization—the slow inversion whereby a person or institution meant to represent the home nation gradually takes on the habits, priorities, and interests of its host. The same dynamic operates in humanitarian and mission networks. It is increasingly difficult to tell where the State Department ends and the mission board begins, or where a gospel of grace ends and the gospel of global justice and limitless consumerism begins.

LCMS Challenges

The LCMS, where nearly nine out of ten dollars originate from voluntary individual or estate giving rather than institutional assessments, reflects these trends vividly. The gulf between its national and international mission budgets is huge.

The Office of International Mission (OIM) now operates at the scale of a mid-tier humanitarian NGO, with ninety-one missionaries and nineteen alliance missionaries across four regions, supported by roughly $15.7 million in direct expenditures and another $12 million in compensation. By contrast, the Office of National Mission (ONM) spent only $5.2 million on all U.S. ministries. The ratio is roughly three to one in favor of international work, even though the LCMS’s domestic footprint—1.67 million baptized members and 5,700 congregations—dwarfs its overseas presence.2

By contrast, the ONM report reads like a factory ledger: resource-rationing, cost-cutting, efficiency measures. Programs depend heavily on outside grants—most notably two from the Lilly Endowment for youth and worship formation. Even disaster response shows reliance on ad-hoc donor campaigns: $1.4 million in hurricane grants against $1.67 million spent. By contrast, the OIM’s multi-year FORO partnership model resembles the consortia of international NGOs—again reflecting the cosmopolitan effect, where transnational collaboration seems more scalable (and fundable) than domestic discipleship.

Saving the World While Losing the Homeland

The OIM operates at the scale of a mid-tier humanitarian NGO, while the Office of National Mission—charged with sustaining, at least indirectly, 5,700 congregations and 1.6 million baptized members—runs on barely a third of that funding. The imbalance is neither sustainable nor prudent; it is not how Scripture asks us to steward the resources God has granted to our care and conservation.

Over the past quarter century, the LCMS has fallen from roughly one million weekly worshippers to perhaps four hundred thousand—a contraction that no overseas expansion can offset or justify. Each closed congregation weakens the base that funds, prays for, and sends the next generation of missionaries. A globalized church body cannot survive a domestic implosion; its foreign vigor is only ever the reflection of its local health.

The upcoming task of realignment and reprioritization is made more critical by the fact that the LCMS only has ~20 years remaining of large bequest giving - regular giving is already in secular decline.

International work gives the appearance of vitality—vibrant reports, relief projects, photographs of baptisms of exotic looking people. It is emotionally irresistible and easy to fund. Yet it masks a shrinking home front. The LCMS continues to close more congregations than the tenuous onces it plants, depend on aging donors for stability, and sustain operations through large bequests rather than living contributions. The danger is missional inversion: being more visible and vital abroad than alive at home.

The deepest danger is cultural. The American donor instinctively prefers to rescue the world rather than rebuild his own parish. Foreign missions photograph better than Sunday schools. But the church that evangelizes Addis Ababa while neglecting Appalachia will eventually lose both. International work is a derivative instrument: its value depends entirely on the underlying asset—a healthy, catechized, and coherently confessing domestic church.

To remain a church with a viable global footprint, the LCMS must first remain a national one. The task is not withdrawal but rebalancing: global engagement rooted in local vitality. A majority portion of the international spending must revert to domestic catechesis, local evangelism, and Pastoral formation. America itself is once again a mission field. It is now ethnically diverse, post-Christian, and in need of the same mercy services and gospel of grace exported abroad.

The Paradox of American Mercy

The LCMS is not an anomaly but a mirror of the broader American missionary impulse. Whether expressed through churches or NGOs, Americans still believe that moral action must be global, visible, and scalable. It is an admirable instinct, but a dangerous one. The same altruism that built hospitals and schools across continents can also hollow out the institutions that made such generosity possible in the first place.

Foreign missions, humanitarian NGOs, and international activism all feed on a distinctly American faith that the world can be repaired through money, effort, and sincerity. Yet every act of benevolence abroad draws upon a moral economy at home: congregations, communities, donors, and families who still believe that giving matters. When that economy falters, the pipeline of mercy runs dry for everyone.

To hack American altruism is not to exploit it but to discipline it—to tether global ambition to local renewal, revival, and regeneration. Let charity begin at home again. The world needs American generosity rooted in households, congregations, and institutions strong enough to give without losing themselves and their children for the sake of the sojourner or the foreigner.

The LCMS is not thriving at home. It is time for candid reflection about our priorities, and about the first and most enduring mission field: the one inside our own national borders.

☩TW☩

2023 Global Philanthropy Tracker Full Report, https://scholarworks.indianapolis.iu.edu/items/427139fd-e626-4436-aff6-ef91638a915e

LCMS Annual Report 2024, https://files.lcms.org/file/preview/annual-report-2024

The thing you have to take into account here is what is means in the Annual Report when it says “Use of Donor Restricted Net Resources.” From what I understand (and I could be confused about what funds are represented here) the reason that almost all the funding for international missions comes from that category is because OIM currently uses the Network Supported Missionary (NSM) model to support her missionaries. I’m currently serving my vicarage in Puerto Rico but am classified as a missionary of the Synod. As such, I had to fundraise in the US for my own service. Mission advancement also helps us fundraise, but generally speaking, the money that goes to fund my missionary service comes from my fundraising efforts, i.e. I presented at dozens of congregations, and people or congregations sent money to OIM that was earmarked specifically for my support. People gave that money because they wanted to or I convinced them to. I don’t think you’re wrong that we should maybe put more money/effort into domestic mission. But what does that look like? Grandma Schmidt was willing to give me $500 for me to do mission in Puerto Rico, but is she willing to do the same to invest in her own community and what does that look like? Who is she giving that money to? The district? National mission in general? I can attest to the quality of the active LCMS missionaries and alliance missionaries I have met, and in my experience our international mission congregations are some of the most faithful in their word and sacraments ministry (confessional, liturgical, etc.). Can the same be said of Synod national mission and the congregations it supports? Again, I may be confused of what that 15 million number represents, but I believe a majority of that comes from individual missionary NSM support. If I’m incorrect and that 15 million represents funds in addition to NSM funds then someone at OIM needs to explain to me what we spend 15 million dollars on, besides missionaries, and how we can get some of those funds to help our work in Puerto Rico.

Our congregation recently had a vicar heading to the Dominican Republic present on mission work. I'm fairly certain the Synod is trying to get ahead of this when he proactively acknowledged that some might question why the LCMS does foreign missions when there is so much to do domestically? His answer to this was simply that domestic and foreign missions are not at odds and that we can do both. But, of course, this intentionally ignores that we can't do both. Resources are limited, so we can't do it all. And where you direct your resources says something.

And as you indicate, I don't see any indication that the foreign missions we have will one day return the favor so to speak by sending resources back to the US to revive the church here. If we don't do it, it won't be done.

There is also a clear refusal to respond to criticisms for directing mission resources to places that are arguably more Christian than our own communities. The Dominican Republic has Roman Catholicism as its state religion, 90% identify as Christian with 60% being Roman Catholic. Those are numbers that I don't think you can find anywhere in the US. So are we just there to "convert" from other denominations? How do we choose our foreign mission locations? There are many cases where looking at demographics of Christian presence already there doesn't seem to make sense to someone on the outside.