Proposition Nation, Proposition Church: Identity Crises of Past, Present, & Future

How the "American idea" and the Protestant ideal are difficult for Lutherans to reconcile and manage in the tension between remaining faithful to Scripture and proclaiming the gospel.

Across both politics and religion in modern America, we are haunted by the illusion that people can thrive on ideas alone. Our civic creed declares that America is an “idea”, while many churches treat faith as a mere checklist of doctrinal positions. Yet as both estates show signs of exhaustion, the shared intellectual flaw of the Proposition Nation and the Proposition Church becomes clear: neither a republic nor a confessional church can endure without an ethnos, a people shaped by shared families, earned history, cultivated traditions, and an unambiguous mainstream religious confession spanning multiple generations.

Among all American denominations, Lutherans, particularly the LCMS, stand out for carrying the cost of maintaining an ‘embodied faith’ in a nation whose melting pot chefs are determined only to recognize a propositional foundation. The theology of the Lutherans is profoundly incarnational, yet their ethnic, cultural, and linguistic distinctiveness has made them awkward outsiders in the Anglo-Protestant origins of America and its federal and state constitutions.

Consequently, this essay explores the parallels between civic and ecclesial propositionalism, traces how American Lutheranism became both rigorous and insular, and considers how the very integrity that preserves it also retards its evangelistic reach. There is no easy compromise, and that is not necessarily bad, wrong, or sinful.

The Propositional Error in the State and the Church

The line “America is an idea” has become the civil religion of our managerial class—a creed that worships abstractions while despising inheritance. Propositionalism drains the nation of memory and marrow, leaving only a husk of liberty and equality without the culture that once created and sustained them. The Constitution is a product of the people; the people are not a product of the Constitution. It can work nowhere else.

Advocates claim that America’s essence lies in allegiance to these principles, allowing anyone who affirms them to belong. Critics, however, warn that this turns the nation into a “cardboard cutout version of a people”—an abstraction without hearth, language, or memory.

The Founders themselves rejected such a notion. John Jay, in Federalist No. 2, wrote that America was “one united people… descended from the same ancestors, speaking the same language, professing the same religion, attached to the same principles of government.” James Madison, in Federalist No. 14, spoke of “kindred blood” and “chords of affection” as the sinews that bound the nation together. For them, political principles required embodiment in a particular people—what Aristotle might have called form and matter united. Without that social matter, even noble and apparently universal ideas degrade into useless abstraction. What the Founders knew of nations, the Reformers knew of the church: the truth of Scripture must take form in and inhabit the people who express and live it1.

American Christianity has mirrored this same tendency. Much of modern Protestantism—especially its revivalist and evangelical forms—presents faith as a series of propositions: Jesus died for your sins; accept Him personally; the Bible is true. These affirmations are sound, yet detached from the church’s embodied life—its liturgy, sacraments, and communal rhythm—they become what J. Gresham Machen called “a ghost of religion, without its body.” Propositional Christianity offers belief without belonging, clarity without culture.

The underlying flaw in both civic and religious forms is ontological individualism—the belief that communities are merely aggregations of autonomous individuals. But propositions, however true, cannot sustain a people. They have no power to shape homes, habits, or worship. Both nation and church require embodiment: a shared life in which the community at every level incarnates practice, ritual, and affection. When belief ceases to take flesh (in a very literal sense for Lutherans), both polity and piety disintegrate literally.

Lutheran Origins: Outsiders to the Anglo-American Heritage

America’s founding culture was deeply Anglo-Protestant, shaped by English common law, culture, and history, overlaid with Puritan and Presbyterian theology and sensibilities. Lutheranism entered as a related, but very distant cousin, first through Swedish settlers at Fort Christina (1638) and Dutch congregations in New Amsterdam, and later through German and Scandinavian immigrants who brought with them a robust confessional tradition.

The Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod (LCMS), founded in 1847, was built by Saxon immigrants fleeing the Prussian Union (the state-enforced merger of Lutheran and Reformed churches). Led by C. F. W. Walther, these settlers established a church rooted in doctrinal precision and bellicose resistance to compromise. Overarching the theological battle array was a sense of being under siege in their home country and under suspicion in their adopted country. Their ecclesiology defined the church not as a voluntary association of individuals but as the body of Christ gathered by Word and Sacrament. In other words, it was a community indivisible from its religious practices and expressions.

The Wends, a Slavic culture from Lusatia in eastern Germany, faced the same Prussian oppression. To capitulate would erase the Lutheranism that made their culture unique, just as it would also erase the culture that made their Lutheranism unique. Religion, culture, family, and folkways were indivisible and inseparable. No niche compromise could save the whole or each individually.

For the Saxons and the Wends, their faith was alive in an entirely concrete sense. They embodied liberty in reality, a continuity of ancestry, tradition, and history that was cherished and opposite to the abstractions the elite would have us adopt. Continuity of ancestry and tradition, not abstract ideals.

Unlike Puritans and Presbyterians, whose religious identity and traditions were, in a sense, automatically entwined with America’s democratic, voluntaristic culture, the LCMS brought with it a liturgy, catechism, and musical canon rooted in centuries of Germanic folkways. Its faith was incarnational, not propositional, reflecting Martin Luther’s Large Catechism describing the church as “a Christian holy people” in which the Word is “preached, believed, professed, and lived.”

This incarnational insistence also made Lutherans defensive. Having fled forced unionism in Europe, they faced new pressures in America—from revivalism, moralism, and the push for interdenominational unity. The Tennessee Synod, founded in 1820 under David Henkel, resisted the proposed General Synod for fear it would become a “political union” that reduced doctrine to majority vote. Charles Porterfield Krauth, later, gave intellectual form to that resistance, arguing in The Conservative Reformation and Its Theology (1871) that Lutheranism’s power lay precisely in its embodied confession—a faith inseparable from its liturgy, sacraments, and historic continuity. However, Henkel and Krauth did not have the same ethnos in mind as teachers of their particular sphere of the church. They were embedded “heritage Americans” who happened to be in a minority protestant denomination that had limited access to power (influencing the State).

By the twentieth century, the defensive posture of the German and Scandinavian Lutherans had crystallized into a very distinct Lutheran ethnos, which remains intact at its core in 2025. To compound this enculturation, that ethnos was primarily rural and involved in farming. In the cities, civic leaders reinforced this cohesion through newspapers and literature in their specific vernacular. The church vernacular was even more comprehensive with a formal liturgy in the local language, parochial schools, tightly managed publishing houses, and folk customs such as Reformation festivals and Wurstfests. These practices preserved identity amid assimilation, but they also set and kept Lutheranism apart from the main currents of American Anglo Protestantism.

The Saxons and Wends understood what our propositional age forgets: that faith and liberty must live in the flesh, not just in the mind. Their flight from Prussian unionism was both a migration and a confession in motion, stating that faith abstracted from culture and history is to lose the first half of the battle.

Wherever Germanic peoples have settled abroad, similar conservation efforts are visible. Argentina, Brazil, Canada, South Africa, and Namibia all exhibit these intense fusions to create a distinct ethnos that has an enviable self-preservation and perpetuation mechanism, which the global elite has now dismantled in the mother country.

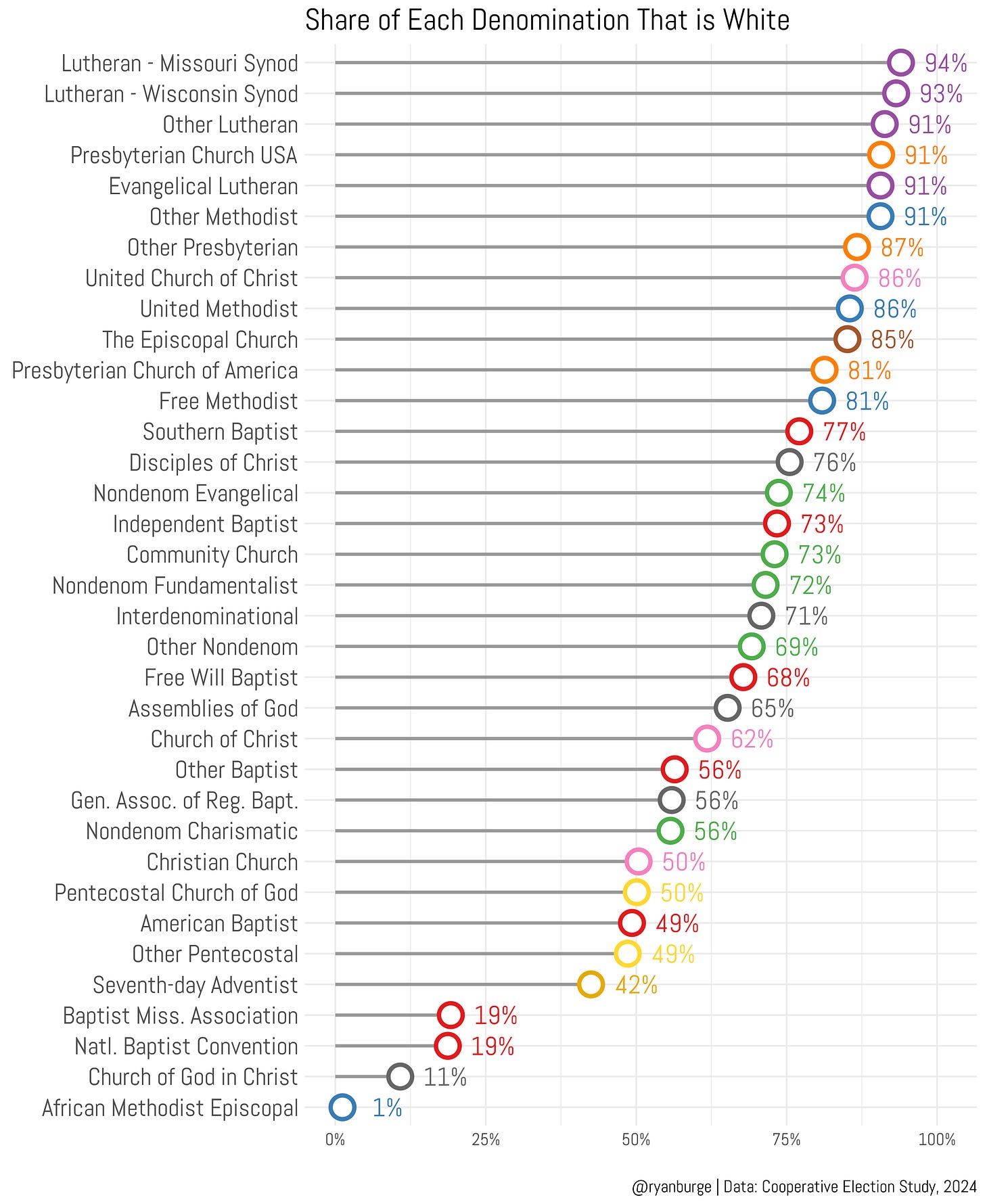

Consequently, we should not be surprised or ashamed that the LCMS is 94% white; America’s barbell to the African Methodist Episcopal Church being 99% black.

Theological Siege Castles and the Drag on Evangelism

The deep commitment to maintaining doctrinal purity in tandem with an ethnic and cultural foundation creates what might be called ‘the drag of embodiment’. That is not a flaw but a feature of an incarnational faith. It is a form of theological realpolitik that guards the altar from dilution, but it also slows the spread of the faith because Lutheranism is, in many senses, in continual tension to resist corruption and commodification. Safeguarding doctrinal integrity is the prime directive, and that will drive very specific behaviors and outcomes.

As we saw with the General Synod, doctrinal purity seems to be mutually exclusive from assimilation and rapid expansion. To be Lutheran is not merely to affirm a creed but to inhabit a culture: specific patterns of worship, song, and catechesis rooted in sixteenth-century Saxony and seventeenth-century hymnody.

The culture has tried to modernize and adapt, but with great care to prioritize conservation over innovation. It is an amazing church sociological phenomenon to see this playing out even today in the LCMS, as evidenced by the intense contemporary culture war over The Lutheran Hymnal (TLH) versus the Lutheran Service Book (LSB). The LSB has a much more substantial Anglo influence if you only count the Catherine Winkworth hymns, but the depth of feeling about the LSB’s “betrayal” of historic Missouri is remarkable.

Assimilating new converts, therefore, means more than teaching cold, hard doctrine; it means inducting them into a way of life. In this sense, the LCMS’s evangelistic challenge is unusually unique: how to reach and make new believers without dissolving the specific folkways that define the Synod. LCMS cohesion fosters doctrinal clarity and unity, but that also projects an exclusionary and exclusivist culture, which the gods of this age are very set against.

The Persistent Twin Temptations: Simplification and Insularity

Lutherans face two perennial temptations:

The first is simplification—to imitate broader evangelicalism’s marketable minimalism. The nineteenth-century General Synod under Samuel Simon Schmucker’s Definite Synodical Platform (1855) pursued this course, softening doctrines such as the Real Presence and baptismal regeneration to align with generic Protestantism. Such reductionism promised growth but risked losing Lutheranism’s embodiment that would have turned the faith into a formless blob on the sea of American religious innovation.

The second temptation is insularity—to equate confessional fidelity with cultural uniformity. The LCMS’s demographic homogeneity has long mirrored its immigrant roots, but it makes evangelism very challenging both at home and abroad.

Inwardness and Outreach

The LCMS’s inwardness is not hokey cultural nostalgia or deep-seated racism, but the inevitable byproduct of theological defensiveness. Confessional German and Scandinavian American Lutherans have never ceased resisting the threats of unionism (forever echoing from Prussia) and American revivalism (forever seeing Charles Finney around every corner) as they seek to preserve the church’s sacramental center.

Whether the inwardness has hardened into isolation is up for debate. Critics sometimes conflate Lutheran coherence with ethnocentrism, misunderstanding that its unity arises primarily from confession, and secondly, family and tribe (but never bloodline). However, it seems clear that conversion is mainly a task of ingestion before outreach. Converts arrive at the church door more than Lutheran missionaries and pastors show up at their doors. This process is not because the church is exclusionary; it is simply an artefact of the idiom of LCMS, WELS, and ELS Lutheranism. There is a high bar to be a Lutheran in America because you are not only taking on the theology, but the culture. The converts are necessarily all Ruths needing a Boaz to bring us into the ethnos.

The massive challenge for the LCMS is how to translate its Lutheranism to and for other people. You cannot simply take the LCMS template to Kentucky, much less Kyrgyzstan. Each place requires a unique Lutheran idiom, a translation of the German Midwest church to a local cultural accent. That is not something the LCMS, WELS, or ELS has managed to do with much success, and it is because there is a continual tension between the risk of losing the syntax of an unabridged and faithful Lutheran confession that avoids cultural dissolution, which will destroy the remaining confessional Synods.

When Ideas Take Flesh

The LCMS mirrors the nation it is embedded in. Both were born in pursuit of freedom, one political, the other theological, and both are tempted to forget that propositional freedom is the recipe for chaos. A creed without a people, like a constitution without a cultural heritage, becomes a spectral parchment.

Lutheranism’s peculiar strength has always been its refusal to live within disembodied slogans. Its insistence on the Bible, the altar, the font, and the pulpit as tangible, yet ordinary, places and things has been a constant resistance to being forced to flatten itself into whatever modernity demands. A faith that insists on incarnation cannot be mass-produced. It must be learned, sung, eaten, and passed from father to son, mother to child, congregation to convert. Making converts is very hard because they must necessarily find the church rather than be found. We depend on real relationships and people, just as we depend on a real body and real blood to sustain and fortify our faith. The sacraments are not propositional and our lives and nation are just as rooted in real and ordinary things.

The task before the LCMS is therefore not to invent a new strategy, but to remember itself first. Every culture that receives the Word must see, taste, and hear it in its own tongue and idiom, yet recognize that it is the same Word that came down from heaven and took on flesh. It’s not clear that we have really figured out how to do this.

In the end, a nation without hearths and families, and churches without doctrines and altars will both become ghosts of memory.

Sources & Further Reading

Ben R. Crenshaw & Mike Sabo, “The Myth of the Propositional Nation” (American Reformer, 2024)

Michael P. Zuckert, “Race and the Propositional Nation” (National Affairs, Fall 2022)

James R. Wood, “Whose Heritage? Which Americans?” (Ad Fontes Journal, 2024)

“America Is Not a Proposition Nation” (American Renaissance, 2017)

“The Propositional Nation Myth Crumbles Under Real-World Tests” (The Blaze)

Martin Luther, Large Catechism (Christian Classics Ethereal Library)

Charles Porterfield Krauth, The Conservative Reformation and Its Theology (1871)

David Henkel, Objections to the Constitution of the General Synod (1821)

Socrates Henkel, History of the Evangelical Lutheran Tennessee Synod (1890)

Concordia Historical Institute, “Walther’s 1847 Kirchengesangbuch”

This is a strong clue about what Barthian Lutherans slide into antinomianism.

Excellent article. Thank you!

Lusatia was a region in Saxony, not Prussia, and thus was not under strict Prussian Union enforcement. The Wends left Germany for three main reasons: (1) rationalism and unionism tendencies in Saxony that threatened their Lutheran faith; (2) the threat of losing their Slavic language and social culture to the German language and culture where they lived; and (3) the economic hardships that were happening to them at that time.

Ironically, when they arrived in Texas, the Wends settled in a community of German Lutheran immigrants, resulting in their Pastor Johann Killian having to hold separate Wendish and German services. Later, the Wends joined with Walther and the Die Deutsche Evangelisch-Lutherische Synode von Missouri, Ohio, und andern Staaten.