Missouri's Disappointing Biblical Authority "Great Debate"

Can the laity handle textual instability when it comes to the Bible?

There is surprising discomfort when Christians ask questions about how the Bible came to exist in the versions we rely on today. Superficially for the laity, some believe that the Scriptures we read are just facsimiles of the original Old Testament and New Testament that some museum has locked up in a vault. However, there is also a fear that asking hard questions about sources and how the Biblical canon came to be compiled risks being accused of undermining the authority, inspiration, inerrancy, and infallibility of Holy Scripture.

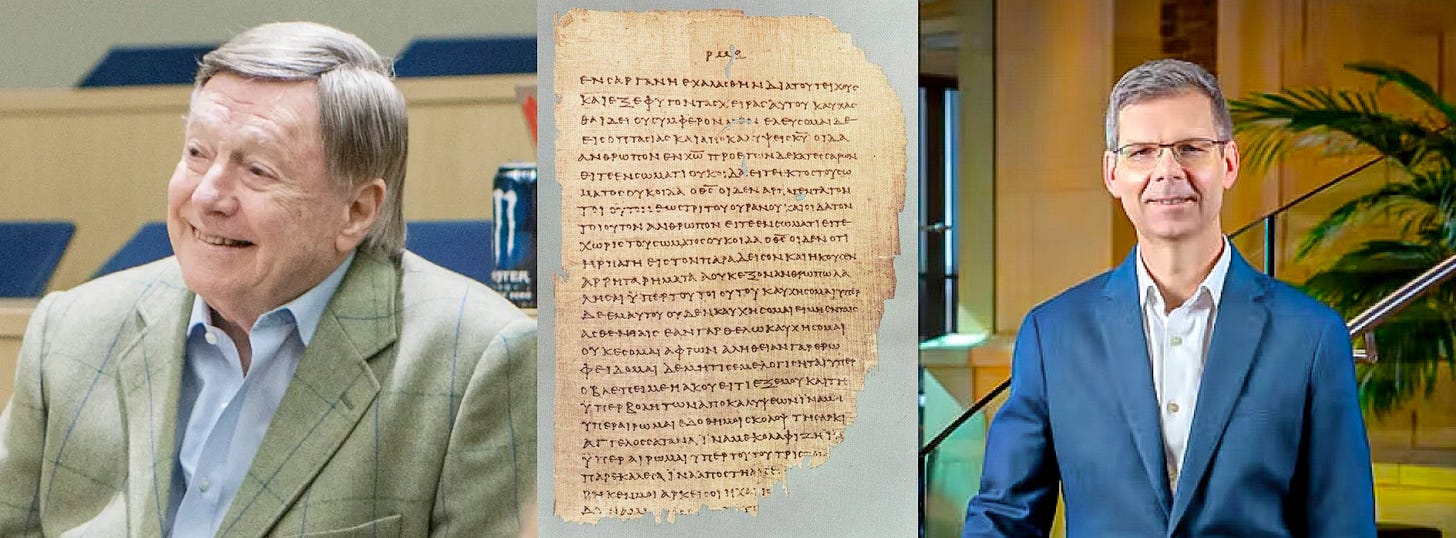

In that context, the 2016 debate between Rev. Dr. Jeff Kloha, then provost and professor of exegetical theology at Concordia Seminary, St. Louis (CSL), and Dr. John Warwick Montgomery promised to be a defining moment. Unfortunately, it did not provide any hoped-for resolution about the trustworthiness of our Scriptures.

Recap

The “plastic text" controversy erupted after Kloha's draft academic paper, “Inspiration, Authority, and a Plastic Text," presented at a closed event in Oberursel, Germany, was leaked online in November 2013. The term "plastic text" refers to the idea that the New Testament (NT) text is malleable due to ongoing revisions in textual criticism, a field where scholars analyze manuscript variants to establish the most reliable biblical text.

Soon, a broad swathe of the Synod was convinced St. Louis was again dabbling in historical-critical subversion.

Superficially, there was reason for alarm since Kloha did make some controversial statements about things we take for granted, such as Elizabeth, rather than Mary being the author of the Magnificat. However, in full context, many of the statements seemed hyperbolic, perhaps even needlessly provocative, in service of Kloha’s apparent concern that scholars were too eager to make the NT “dynamic” based on new manuscript discoveries and scholarly analysis.

My 2013 layman’s reading came away thinking he was sounding the alarm about developments among the “experts” responsible for assessing and assembling our foundational NT texts rather than declaring, “Did God really say…?” I interpreted Kloha as telling us to get ready for textual specialists to try to rock our world with manipulation of the NT but that nothing they did could sway us from the certainties of the Gospel or the foundational authority of the Scriptures we already possess and deploy. I was, and probably still am, in the minority.

The fallout compelled Synod’s leadership to act. President Matthew Harrison, then CSL President Dale Meyer, and Synod VP Rev. Daniel Preus met with Kloha and found “No false teaching in the revised paper.” A final revised version was never published, which did not help ease suspicions.

The Debate

The “plastic text” blowup peaked in October 2016 when Kloha and Warwick Montgomery engaged in a formal debate at Concordia University Chicago (video embedded below). I had some minor involvement, having facilitated a debate transcript long before AI made such things easy. The scholarly clash received top billing and was highly anticipated, but it fizzled into a frustrating mess.

Kloha defended his use of “thoroughgoing eclecticism,” which involves detailed internal and external evidence analysis to determine the most reliable text when there are variants. He argued that this approach was consistent with historical practices and necessary for maintaining the integrity of Scripture in light of new manuscript discoveries.

Montgomery was relentlessly critical of “thoroughgoing eclecticism” for its reliance on subjective internal criteria, such as literary style and theology, which he argued would undermine the authority and inerrancy of the Scriptures. He advocated for prioritizing external manuscript evidence and expressed concern that Kloha's approach could lead to a destabilized and continuously changing text, which would be problematic for doctrinal certainty and the authority of the Bible.

The debate was unsatisfyingly inconclusive. Montgomery was too prosecutorial and seemed to lapse into using Kloha’s methods to defend some of his positions on specific texts.1 Kloha became increasingly defensive, frustrated, and even exasperated. Ultimately, the two men talked straight past each other, and the audience was the loser.

They had fundamentally different approaches and priorities regarding textual criticism, contributing to miscommunication and misunderstanding. Both scholars quite narrowly referenced their own frameworks and assumptions, sometimes addressing various aspects of the issue without fully engaging with each other's core arguments. For example, Kloha emphasized the scholarly necessity of his method, while Montgomery focused on the potential theological implications and the need for a stable, authoritative text. Similarly, Kloha’s encyclopedic knowledge of the manuscripts and the languages contrasted with Montgomery’s courtroom-style presentation and arrangement of third-party evidence.

They never got to the brass tacks—was Kloha guilty or not guilty of destabilizing the NT and thereby promoting false doctrine or at least undermining established dogma? The debate devolved into an inability to reconcile their perspectives or address each other's concerns in a way that bridged their methodological and theological divides.

The debate would have benefited from an independent scholar synthesizing the two main concerns, at least as I interpreted them: a) the Holy Christian Church was being endangered by a loss of trust in the Bible caused by an objectional method of textual analysis, b) universal Christian dogma was being upended by surreptitious expert-driven elevations of alternative manuscript interpretations, which then make their way into new editions of our Bibles.

Let’s Gain Independence

The laity is already sensitive to a degree of “popular” textual instability — KJV only; notes in the Study Bible about verse variants; the Apocrypha for some but not others; the Septuagint for the Eastern Orthodox but the Masoretic for the West; revelations from the Dead Sea Scrolls; the Gospel of Thomas; and the nonsense Gospel of Mary, etc. to name a few. The laity can handle robust debate on the issue without their faith falling apart. If anything, we need more information from our Lutheran experts about how we got our Scriptures and why we should trust the Biblical canon in the face of new manuscript discoveries, interpretations, and run-of-the-mill subversion.

The LCMS has the academic firepower to produce its own English Bible translation. This would be the most effective way to deal with questions of textual stability and Biblical authority. What can be better than the Synod’s seminaries and universities being accountable and accessible for coping with newly discovered variants, ongoing translation disagreements, and interpretation ambiguity?

The Synod is at the mercy of copyright owners of translations such as the English Standard Version (ESV).2 There would be no more excellent gift to the church than delivering an independent translation that Lutherans can be proud of, from which all our pastors preach, and the Evangelical Lutheran church bodies can distribute liberally.

CPH cites this reason for being unable to release the Small Catechism into the public domain.

“The LCMS has the academic firepower to produce its own English Bible translation.”

I’ve long thought the same. And that WELS/NPH has done it (EHV) despite their size disadvantage just goes to further prove the point.

At this point, I don’t share your optimism. Their treatment of our symbolic books over the year doesn’t suggest to me that they have the capabilities to take on a more weighty project like a translation of Scripture. And no, I’m not just talking about the latest endeavor with the Large Catechism, but also to their treatment of the Small Catechism and the Book of Concord. The Small Catechism has been weighed down with bloat and less helpful translations. The Book of Concord readers edition was in many ways a narrowing of the information provided to the Church. Even the Lutheran study Bible is not something that I would say indicates they are up to the task of doing a new translation of Scripture. To be clear, I like and use the Lutheran study Bible, Book of Concord readers edition, etc. alongside other resources. But I don’t think they demonstrate the capabilities to do what you suggest. I hope I am wrong though.