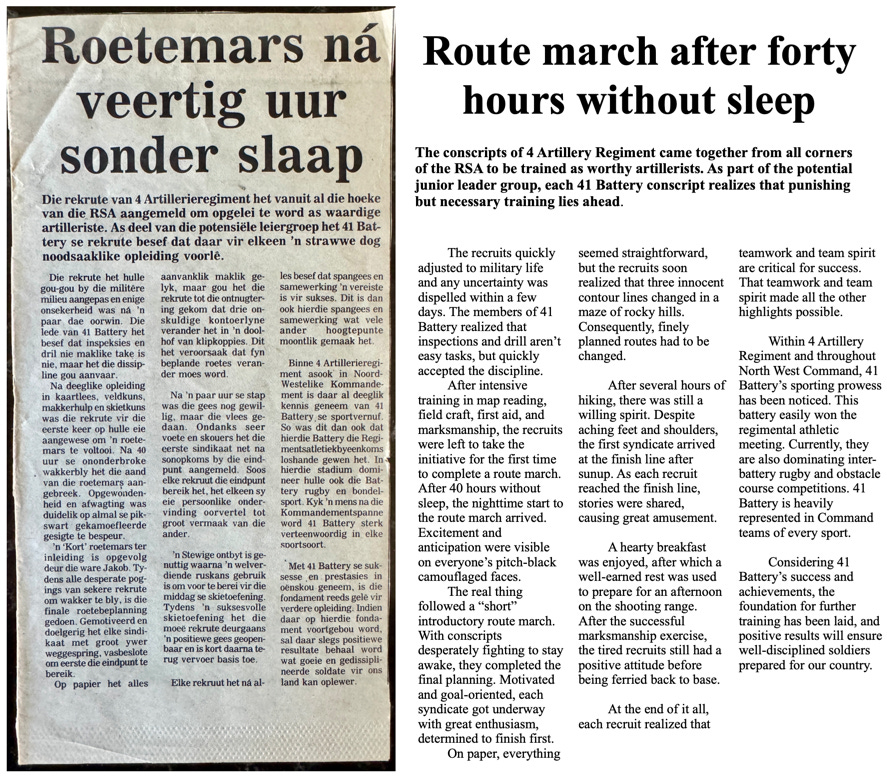

Lore Stories: War Stories, Part 1 - Basic Training

A tale of state slavery as a conscript in the South African Defence Force.

My final day as a conscript in the South African Defence Force (SADF) was mid-November 1988, with an uitklaar parade (demobilization parade) on a dusty, stony red parade ground in Potchefstroom (Potch)1. The parade was perfunctory - the inverse of the pomp and circumstance of the “passing out parades” for completing basic training and the Junior Leader course, because the “PFs” (permanent force) were already dealing with our escalating petty insubordination as we grew more resentful of marking time instead of being released to civilian life.

At least we were getting out a month early, thanks to the ceasefire in Angola ahead of the implementation of UN Resolution 435. As part of the demob, Pro Patria medals were to be pinned on everyone who had served in the “operational area” - Angola and South West Africa (Namibia today). However, only Afrikaners got their medals that day to ensure we remembered who was in charge. The Englishmen and other foreigners received their dime-store medals over a year later. The English cohort laughed once we realized the game, lazily executed the final parade commands, and walked out the camp gates for the last time, vowing never to return.2

Ahead lay a welcome two-month break to adjust to civilian life before starting classes at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits, pronounced Vits), where I would meet my future wife soon after arriving on campus.

Big guns or little guns?

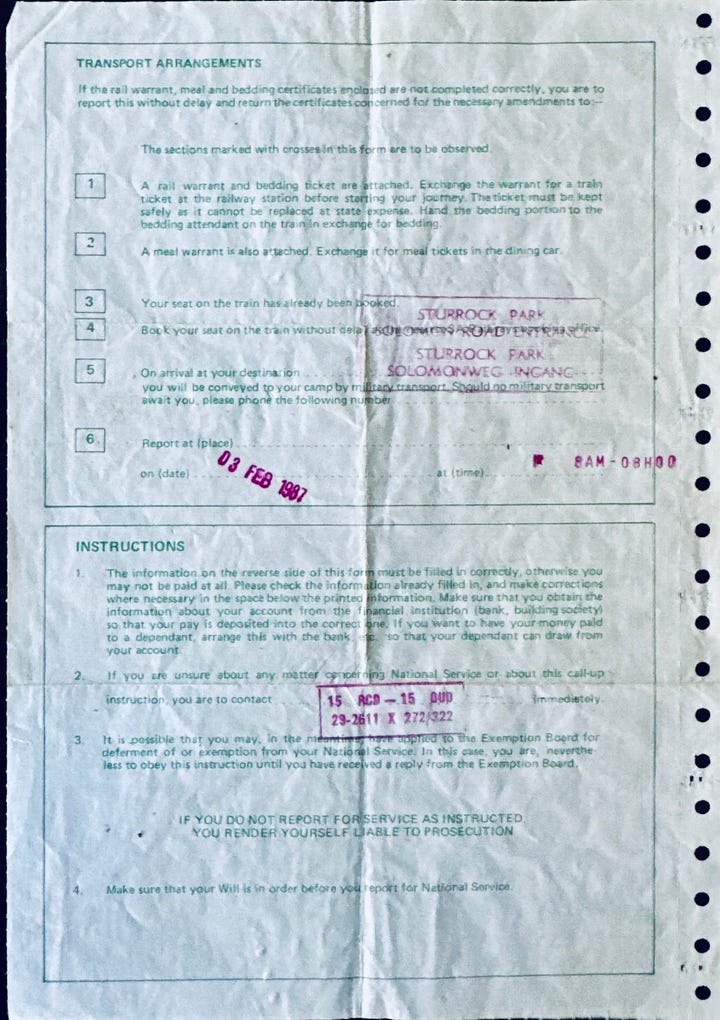

21 months before uitklaar, it was the dreaded aanmelding (mustering) day - Monday, February 3, 1987, 08h00. Thousands of boys would show up to start two years of compulsory National Service (a small percentage of each year’s intake began in July). Up to 1988, the protocol was for families to drop off their sons for a final farewell at the Sturrock Park stadium, and then watch them march to trains at nearby Braamfontein Station that would carry them to bases all over the country. My farewell was truncated - an epic Johannesburg thunderstorm was underway, which was snarling rush hour and made worse by the military traffic. We were way past late, so it was a quick goodbye to my parents, and I grabbed my bag, ran along the highway, and made it into the stadium without being dead last.

No sooner had I sat down, sopping wet, when the worst Afrikaans attempt at English boomed over a tannoy, “Timuhfhee Hoood, mags nommer (force number) 8454****, come to here!” My whole plan to be in the middle of the pack at all times ended right there. I obediently trekked to stand in front of an ominously large and impressively mustachioed man with stripes on his arms.

He asked for my call-up papers and compared them with another set before handing all of them to me. “Tell for me now, go you Potchefstroom of Youngsfield?” Somehow, I had duplicate call-up papers—one to 10 Artillery Brigade in Potch, which had been mailed to the house, and a mystery one to 10 Anti-Aircraft Regiment, just outside Cape Town. There was hardly a decision to make; I had zero interest in being 1,400 kilometers (870 miles) from home, which made weekend passes impossible to use since you had to hitchhike both directions. Potch allowed you to be home by early evening on Friday, and leave Joburg at the last minute to arrive at the guard gate by 20h00 on Sunday.

In addition to being reasonably close to home, I was relieved to have avoided the infantry brigades and JL training at South African Infantry School in Oudtshoorn, to which most of my school friends had been shipped.

National Service

National Service was compulsory for all white males aged 16 and over. Service was deferred as long as you were in high school or university. After basic training and passing the Junior Leader (“JLs”) course, university graduates were guaranteed a commission as full lieutenants.3 Still, most boys wanted to get it over and done with, so the vast majority started about a month and a half after final year (matric) exams, aged 18. Volunteer units from other races supplemented the conscripts along with graduates from the tiny women’s army college.

There were some options if you didn’t want to go to the army for two years (only a tiny percentage were accepted to the navy and air force, because those branches had a very high ratio of permanent force (career) personnel):

Being medically unfit (the bar for “G5K5” exemption was very high - if you could peel potatoes in a kitchen, you were doing National Service).

Three years in the South African Police (SAP).

Six years in prison for conscientious objectors who didn’t manage to flee the country.

Ten years in “civil service” such as the South African Post Office or a city fire brigade.

From 1984, white male immigrants (mainly from the UK, Portugal - mostly via Angola and Mozambique, Greece, Cyprus, Italy, and Germany) lost their exemption and were also conscripted.

If your parents were part of the power elite, they would call in favors to get you posted to one of Voortrekkerhoogte’s (Pretoria) many non-combat administrative units, which were highly prized, except for the ridiculous color of their berets.

In my year, it backfired spectacularly for the sons of the well-to-do and sundry politicians. A week into basic training, busloads of very downcast boys arrived from Pretoria because the process's corruption had reached ridiculous levels, swamping the capital city with a vast surplus of soft draft dodgers.

After completing National Service, you were on the hook for ten more years in the Citizen Force and could be compelled to serve 90 days each year. It was rare for anyone to serve that intensively, but mechanics seemed to bear the brunt of the demand with repeated call-ups of 90 days. Otherwise, the tempo was generally 30 days every two years for combat units to ensure they maintained lethality. In 1985 and 1986, increasing demand was placed on the citizen force and some National Service units to undertake riot control in the “townships” in infantry roles, as the low-intensity civil war ebbed and flowed.

In 1993, I received a call-up from my Citizen Force unit, the Transvaal Horse Artillery (THA, since renamed Sandfontein Artillery Regiment), essentially a home for gunners attending or affiliated with Wits University. I ignored it, and there were no consequences because Apartheid was winding down quickly, with no capacity to pursue guys who were AWOL.

Basic training

After thoroughly searching everyone and their belongings for contraband, it was a relatively short trip to Potch on a train with steel shutters on the windows to discourage anyone from developing a last-minute change of heart and mind. Everyone seemed surprisingly easygoing… until we had to disembark. The barked commands were endless, rapid-fire, and meaningless because everything was in Afrikaans, which I only understood at slow speed. That was thanks to boarding school in Britain’s “Last Outpost”, Natal Province. That also meant I had not done “Cadets” - paramilitary training and indoctrination for high school boys who were supposed to do uniformed drills, lessons, shooting, and band at least once a week.

Interestingly, SA artillery and anti-aircraft were relatively English-coded, reflecting more of Britain’s Royal Artillery heritage than the Boers' success with the French-made 155 mm Creusot “Long Tom” siege guns.4 That translated into a welcome overrepresentation of conscripts from Durban and the English suburbs of Joburg and Cape Town. Nevertheless, everything was conducted in Afrikaans, so you either caught on quickly or spent a lot of time running, lifting rocks, carrying steel fire buckets filled with sand, and doing endless pushups.

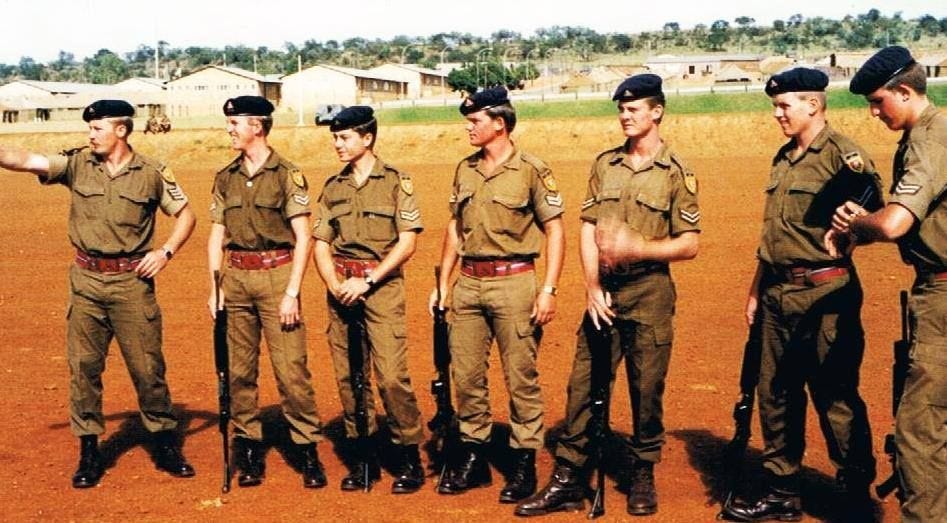

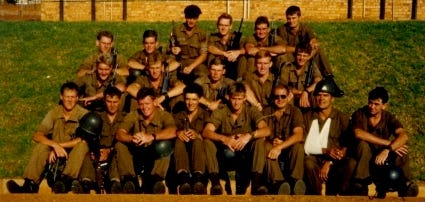

Intake

Conscripts were processed into their batteries after being driven in trucks to the camp from Potch railway station. The brigade took a streaming approach to assignments that year, with those initially earmarked for Junior Leader training (JLs) going to 41 (Papa) Battery, 4 Artillery Regiment.5 By the end of basic training, other units did send men to JLs, but in sparse numbers compared with Papa BTY, which sent 100% of its gunners to the School of Artillery (“Art School”) to become 1st lieutants (with degrees) or 2nd lieutenants and bombardiers (2 stripe corporals). From the start, it was made clear to everyone in Papa BTY that we were tracking for Art School and were required to dominate every competitive encounter with other batteries, mainly for the battery commander’s ego.

The first week was a blur of medical assessments (dignity and any sense of privacy evaporated as nurses and doctors of both sexes collected blood and urine samples while measuring, prodding, and poking columns of men in their underwear), getting a buzzcut, going to the stores for uniforms and equipment, learning how to get fed and watered (the canteen doubled as the classroom), rules for abluting, where and how to get clothing washed, dried, and ironed, and figuring out friend or foe within your tent and troop.

10 Art Brigade had a huge intake in 1987 and 1988, so many of us ended up in overflow tents rather than bungalows for all of basic training. It was either miserably hot or bitingly cold, and continually dusty (right across from the dirt parade ground). However, the quid pro quo was that we did not have to clean bathrooms, and the inspections were less rigorous.

Routines

Once training started in earnest, it was always “hurry up and wait” mode, but the overall structure was pretty rigid.6 The daily routine was broken up with visits to the shooting range, guard duty (detestable, especially over weekends), regular foot inspections to treat any blisters, major inspections, large sports events against other units in town, Thursday afternoon sports, Sunday church parades, PT tests to assess fitness progress, and several overnight field exercises.

Church parade was always amusing. Men were dismissed to waiting trucks in three groups:

NG Kerk (Dutch Reformed Church) - most of the unit.

Doppers (Gereformeerde Kerk) - a sizeable chunk since Potch University was the denomination’s seminary.

Engelsmanne, sokker spelers, en Metodiste - Englishmen, soccer players, and Methodists.

Raised Baptist, the Methodists had no appeal for me, and the assigned chaplain was ineffective. So, it wasn’t long until I discovered the Wimpy restaurant was a very short walk from the church. Word spread about the “Wimpy Christian Church”, and the number of “Methodist converts” increased rapidly all through basic training, to the annoyance of Reformed stalwarts.

A sports pass was a big deal because it got you out of camp every Thursday afternoon, and more if you were competing seriously. Rugby players and track athletes were royalty and completed very little actual military training - the point was to check a box. If the rugby players weren’t on the field, they were indulging in serious alcoholism. By pretending to play soccer, I got an afternoon a week off, lying in the shade at the side of the fields and devouring snacks and “cooldrinks” (soda) bought from the nearby SAWI store.

Revelations

Basic training was as much a sociological revelation for me as boarding school had been. At boarding school, I came in sustained contact for the first time with kids from immensely wealthy families where the parents boasted professional degrees and jobs at world-class corporations7. It cultivated a lifelong habit of studying people, situations, and institutions as an outsider.

Conscription brought me into new sustained contacts; a majority Afrikaner environment with a strong tribal streak, bridging relationships with graduate students and guys who never made it past 10th grade, hardened criminals, drug and alcohol addicts, men with zero concept of personal or general hygiene, and an IQ distribution impossible to describe.

It was during basic training that I was finally able to articulate what I had begun to understand during Veldskool (Field School) in Standard V (7th grade)8 and during my high school’s Outward Bound modeled program, which included a challenging week of orienteering, obstacle courses, and teamwork problem solving in Standard VIII (10th grade). The ultimate point of those programs, unstated, was to push everyone to the brink and teach vasbyt (stoic endurance).

My realization was that the difference between people who “cracked” and those who did not was entirely psychological and spiritual. It had nothing to do with how athletic or intelligent they were. The guys who cracked thought the present was forever and refused to believe that every bad thing comes to an end. They were not just overwhelmed by recency bias but immediacy bias; they were literally trapped “living in the moment,” and the result was despair. To witness young men break down in a situation where there is no genuine despair is very disquieting, and it had a contagious effect on guys struggling on the margin.

Afrikaners generally had more vasbyt than the English conscripts. It wasn’t hard to develop a respect for those pugnacious people who had a natural talent and affinity for warfare not dissimilar from Dagestanis and Chechens. It was matched with hard drinking and excessive smoking, devouring red meat by the kilo, remarkably creative swearing, elaborate storytelling (bested only by Rhodesians), and a passion for conviviality that devolved when the inevitable pranks went too far. Generally speaking, the South West Africa Afrikaners (Suid Westers) we trained with were on another level of aggression and poor impulse control.

Another realization that firmed up was the reciprocal nature of the “now” personality. The boys who cracked during freshman hazing were the biggest bullies in their senior year at school. The men who cracked in basic training and during the vasbyt segment of JLs were the most determined to find a roofie (newbie) to torment, presumably as a form of attempted shame transfer or shedding. The mercy they begged for in the moment of despair was denied to their targets, a perfect analogue for the parable of the unforgiving servant.

In a final wash-out effort, Papa BTY was sent on a diabolical field exercise that our attention-hungry Battery Commander dreamed up and ensured was in the local newspaper the following week:

It was not the first or the last slight from an ungrateful nation. Five years earlier, my brother had been demobbed with severe, untreated PTSD after surviving a landmine explosion that wrecked the supply truck he was driving, and then getting stuck alone in the Angolan bush waiting for spare parts for his truck. No opportunity for pettiness was missed. I received a punishment drill during basic training for delivering my rifle number in English. Military Police used to hide along the bus route to the mess hall, citing anyone who wasn’t wearing their beret. My mates and I were fined R1,000 each for “speeding” in an IFV on our last day in the operational area. When we were allowed take our mandatory two weeks of leave, the commander refused to give us travel vouchers, forcing us to hitchhike (illegal for commissioned officers) from Oshakati to Windhoek where my parents had an SA Airways ticket waiting to complete the trip to Joburg. My citizen force unit, Transvaal Horse Artillery (THA), discovered that I had never signed the oath of allegiance before officer commissioning. When I declined to sign it at THA, I was informed I would be demoted to Bombardier (corporal).

As a rule of thumb, university deferrals were boys trying to avoid service for many reasons, but often related to fearing the physical demands. Consequently, arriving at camp after several years getting less fit and fatter, many of the grads had a hard time in basic training.

Both countries' “Gunners” motto is Ubique, Latin for “everywhere”. Rudyard Kipling wrote a poem that reflects the Royal Artillery’s tribulations during the Boer War:

UBIQUE

There is a word you often see, pronounce it as you may

“You bike,” “you bykwee,” “ubbikwe “—alludin’ to R.A.

It serves ’Orse, Field, an’ Garrison as motto for a crest,

An’ when you’ve found out all it means I’ll tell you ’alf the rest.

Ubique means the long-range Krupp be’ind the low-range ’ill—

Ubique means you’ll pick it up an’, while you do, stand still.

Ubique means you’ve caught the flash an’ timed it by the sound.

Ubique means five gunners’ ’ash before you’ve loosed a round.

Ubique means Blue Fuse an’ make the ’ole to sink the trail.

Ubique means stand up an’ take the Mauser’s ’alf-mile ’ail.

Ubique means the crazy team not God nor man can ’old.

Ubique means that ’orse’s scream which turns your innards cold!

Ubique means “Bank, ’Olborn, Bank—a penny all the way—

The soothin’, jingle-bump-an’-clank from day to peaceful day.

Ubique means “They’ve caught De Wet, an’ now we shan't be long.”

Ubique means “I much regret, the beggar’s goin’ strong!”

Ubique means the tearin’ drift where, breech-blocks jammed with mud,

The khaki muzzles duck an’ lift across the khaki flood.

Ubique means the dancing plain that changes rocks to Boers.

Ubique means the mirage again an’ shellin’ all outdoors.

Ubique means “Entrain at once for Grootdefeatfontein”!

Ubique means “Off-load your guns”—at midnight in the rain!

Ubique means “More mounted men. Return all guns to store.”

Ubique means the R. A. M. R. Infantillery Corps!

Ubique means that warnin’ grunt the perished linesman knows,

When o’er ’is strung an’ sufferin’ front the shrapnel sprays ’is foes;

An’ as their firin’ dies away the ’usky whisper runs

From lips that ’ave n’t drunk all day: “The Guns! Thank Gawd, the Guns!”

Extreme, depressed, point-blank or short, end-first or any’ow,

From Colesberg Kop to Quagga’s Poort—from Ninety-Nine till now—

By what I’ve ’eard the others tell an’ I in spots ’ave seen,

There’s nothin’ this side ’Eaven or ’Ell Ubique does n’t mean!

In 1987, 4 Art Regiment consisted of:

41 (Papa) Battery: Soltam M-65 120mm Mortar (In some years, Papa battery sent men to 18 Light Regiment, 44 Parachute Brigade, in Bloemfontein for its heavy mortar unit).

42 (Quebec) Battery: G5 155mm Gun/Howitzer.

43 (Romeo) Battery: Valkiri 127mm multiple rocket launcher (automatically relocated to Walvis Bay after Gunnery Training).

Batteries were commanded by a major or a captain, and the 2IC was at least a full lieutenant. They were supported by a battery sergeant major and his 2IC, a sergeant. Each battery was divided into two troops, usually commanded by a permanent force full lieutenant and supported by a permanent force TSM (troop sergeant major), but who was generally a sergeant. Each troop was divided into two platoons commanded by conscript Junior Leaders, usually a full or second lieutenant, supported by a bombardier (corporal).

04h30 am early morning prep for inspection,

physical training (PT),

ablutions,

breakfast (everything slopped onto one varkpan (pig plate), including vile blue eggs) followed by a short break,

inspection,

parade ground drills for two hours with a tea break (glorious sweet milky tea in urns - two “fire buckets” (water bottle holders) per person if your bladder could handle 1 liter/1 quart for the next hour of drills before being allowed to leave the parade ground),

classroom session (desperately trying not to fall asleep and receive a punishment drill),

Lunch with a short break,

Field “classroom” training in a combat rig (rifle, webbing, helmet) was also a form of light PT since everything was done at double time.

Break,

PT,

Ablutions,

Dinner,

Letter parade,

Break (washing, ironing, letter writing, visit to the “tuck shop”, inspection prep etc.),

10h00 lights out.

I was the only student at the school who came from Joburg’s southern suburbs for the five years I was there.

Veldskool was a common program for children in their final year of primary school (grades 1-7). Much has been made of Elon Musk's description of it to biographer Walter Isaacson as a “paramilitary Lord of the Flies.” His recollection is tinged with hyperbole, but the camp was violent because 12-year-old boys from competing schools have tribal instincts when they are thrown together. Overall, my experience was that there was inadequate supervision, and we were far over capacity for the number of boys in camp. The biggest issue was a catastrophic and disgusting hygiene collapse because there was no soap and hot water for the kids to wash their plates and cutlery. Fortunately, I avoided that humiliation by scrubbing my steel plate repeatedly with sand far away from the kitchens.