Lore Stories: Norwegians in South Africa

We get a lot of questions from Americans about how it's possible for whites to be African. Here's one slice of a complicated family history that explains it.

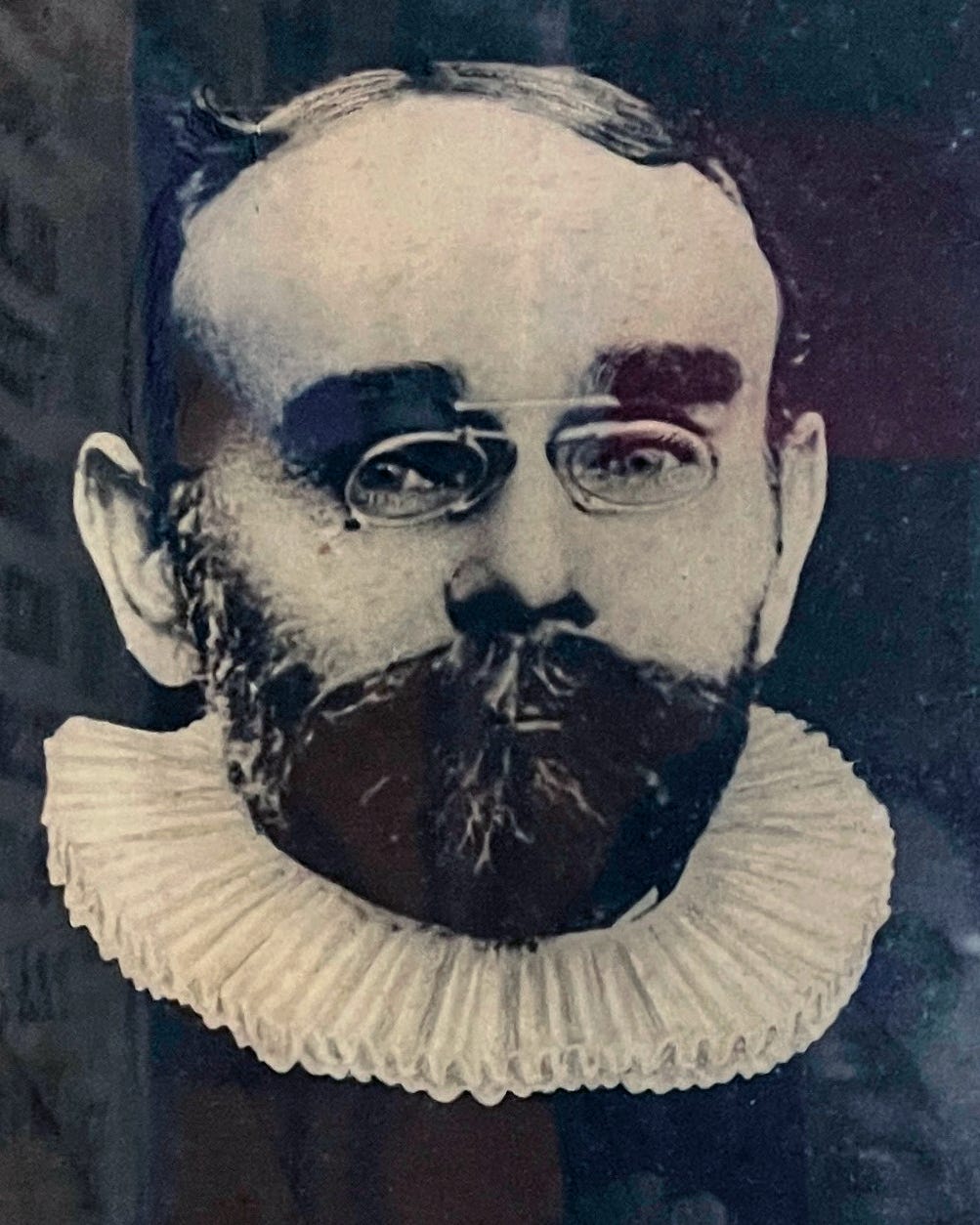

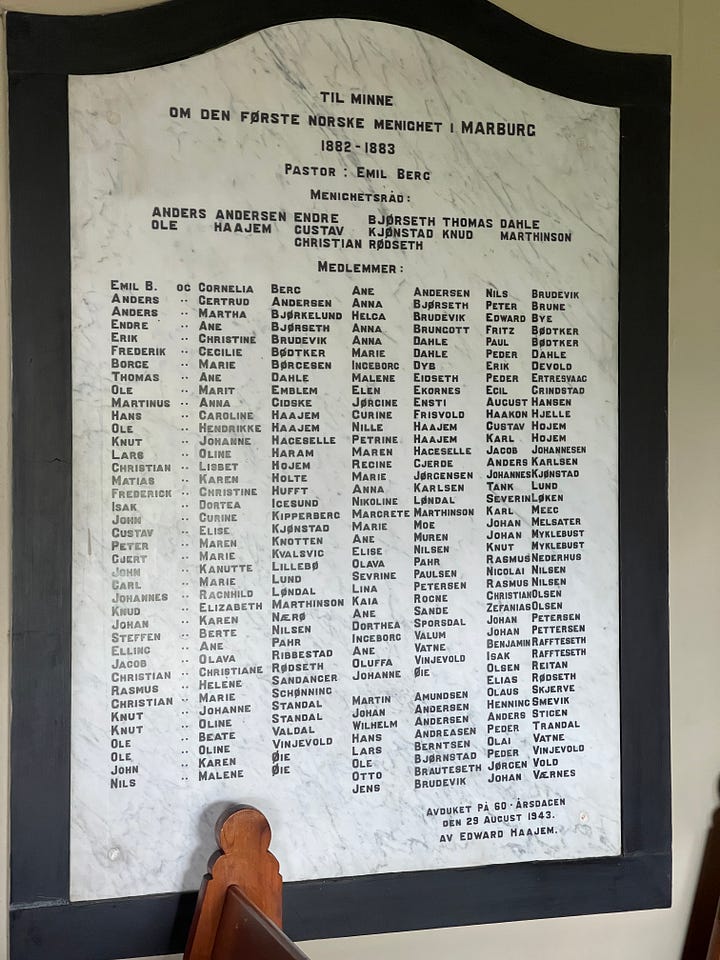

My paternal second great-grandfather, Emil Bernard Berg (1842-1912), was pastor to 230 Norwegian Settlers who sailed on the Lapland to Port Shepstone, Alfred County, Colony of Natal1, arriving on August 28, 1882. Their first order of business was to drag the bell they had brought with them to a hillside site selected for the Norwegian Evangelical Lutheran Church (now the Norwegian Settlers Church) to conduct a Lutheran worship service of thanksgiving and supplication.

Norwegians were leaving Norway in the mid-to-late 19th Century for many reasons, primarily land scarcity caused by a population boom that resulted in subdivided inherited agricultural plots becoming unviable parcels. Farmers suffered soil depletion, poor harvests, and crop price deflation to compound the misery. The potato blight in the 1860s caused famine in some areas. Although industrialization was expanding in Norway, it was inadequate to absorb families leaving the farms, and the cities had deplorable living conditions marked by extreme poverty and frequent epidemics that killed swathes of people. There was also a degree of political repression since Norway was under Danish rule until 1815 and then under the thumb of the Swedes until 1905.

At the time, the Natal Immigration Board was actively recruiting settlers from all over the world for the colony to address labor deficits and shortfalls in agricultural output. Needless to say, the immigration pitch was a little oversold. The promised “comfortable cottages” constructed by the government were crude thatched huts that the local Zulu clans had been paid to build for the immigrants. Natal was not a land of milk and honey and was undeveloped, but the subtropical climate (30.7°S / °30.4 E) was conducive to farming, and they would never experience another harsh winter.

50 plots of 100 acres each were allocated to the families2 (assigned by lot, but with Pr. Berg automatically receiving the central parcel) for farming and communal grazing. The Settlers had to pay for their land over ten years (£1.50 per acre, or approximately 191,064 in 2024 inflation-adjusted US dollars), bring a minimum amount of capital, and provide health certifications from the Norwegian authorities and character references from their home church pastors.

The initial group was followed by 90 families, mainly from the Sunnmøre region, who took up the remaining plots or stayed in Port Shepstone and did not farm.

Settled and Unsettled

When the Settlers left for South Africa, Great-Grandfather Berg was serving as the kappelan (curate assisting the sogneprest, or parish priest) at the Sjømannsmisjon, or Norwegian Seamen’s Mission in Rotherhithe, London. The mission site was near the Surrey Commercial Docks, where thousands of Norwegian sailors plied their trade. The mission eventually built a beautiful church, St. Olav's Kirke, which you can visit today (keep your eyes peeled; it’s not the most salubrious neighborhood).

By one of those strange quirks of history, the Bergs lived two miles south of my maternal grandfather’s family, who lived in the Old Nichol Slum of Shoreditch with the trade of “box makers” (when they weren’t debtor’s prison inmates). Eventually, the descendants ended up 5,600 miles away in Johannesburg and separated again by just two miles.

His curate services had carried him to the Sjømannsmisjon in the centuries-old commercial port of Rotterdam, where he met his wife, Cornelia Schmid3. They were married on August 27, 1867, in Gateshead (Newcastle Upon Tyne) and bounced back and forth between the Sjømannsmisjon headquarters in Bergen, Norway, and the Geordies of Tyneside before moving to London in 1881.

As a curate, Emil was not a regularly ordained Lutheran pastor (lacking a university education?). The Settlers persuaded him to accept a call to be their pastor (perhaps because he was fully bilingual in Norwegian and English and would be an essential interface with the governing British authorities in Natal). Rev. Grondahl ordained him at the Sjømannsmisjon on July 19, 1882, one day before the ship departed London.

The settlers had departed Ålesund on 14 July 1882 aboard the Tasso, arriving in Kingston upon Hull, England. They took a train from Hull to London, where the Lapland awaited them. They departed London on Thursday, July 20, 18824, with a provisioning stop in Dartmouth before they sailed down Africa’s Atlantic seaboard with several more stops to take on coal and food before rounding the Cape of Storms into the Indian Ocean and up to Port Sheptsone.

Pastor Berg traveled with his wife, seven children aged 14 to 4, and two servant girls (probably orphans they had taken in as part charity and part labor with so many young and closely spaced children in the home).5

The Settlers were practical, recruiting a selection of skills and talents to achieve barter-based self-sufficiency. Their collective capital resources were £2,400 (322,374 US dollars in 2024 inflation-adjusted terms), mostly from selling property in Norway. However, only 34 out of 50 intended families made the trip, impairing the settlement’s economic viability as one of several headwinds.

Pastor Berg had no physical trade to contribute, and the agreement was that the settlers would fully subsidize his family. With the community's help, he began constructing the church building, starting with mud bricks made on-site that were later clad with fired bricks (high-quality timber was and is very scarce in SA). The church was consecrated on the first anniversary of their arrival. A school for the Settlers' children was operational by 1884, with the pastor’s wife as one of two teachers.

The original church still stands today. It is beautiful in form and very Norwegian, and the original bell is still in place and working. Unfortunately, the church is no longer an active Lutheran congregation but is adjoined to a reform flavor mega-church enterprise.

Nevertheless, the current church has honored the Settlers’ heritage by preserving the church and maintaining an excellent museum. During a visit in 2022, we asked what had happened to the baptismal font, which was found gathering dust in a storage room. We asked for it to be placed back in the museum, explaining how important it was for the congregation.

The Norwegian Settlers had a tough time making things work because, although the land yielded abundant produce, the produce was too far by road from the key market in Durban, and the government-promised deep water port at Port Shepstone never materialized. Several members left for Durban and other areas with work, putting even more pressure on the community.

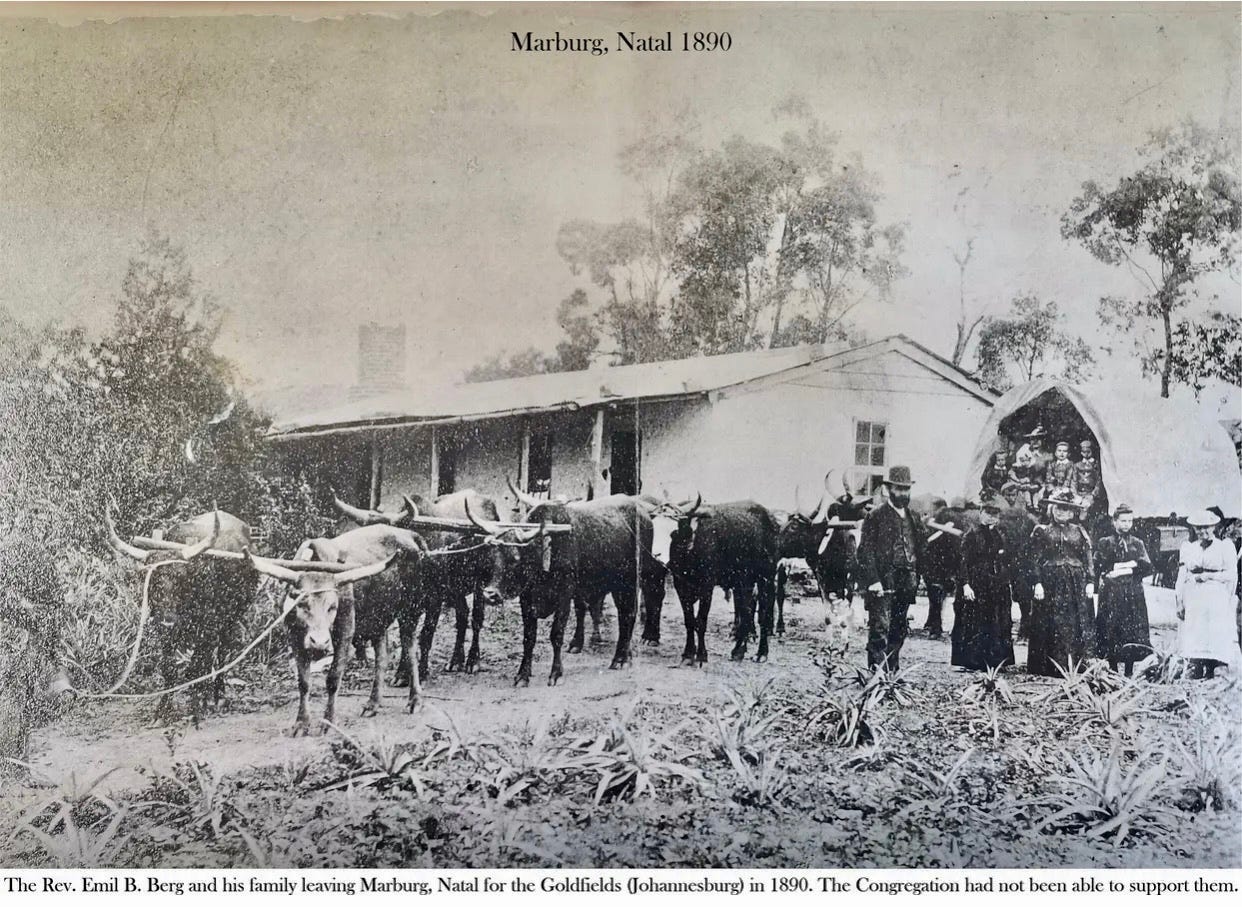

Eventually, the diminished community could no longer support the Bergs. As early as 1884, Pastor Berg had to find work outside the church to feed his family. In 1890, they sold the farm and traveled to the Highveld by ox wagon, hoping to find a livelihood in the great Witwatersrand Gold Rush, which was still gathering pace (discovered in 1886).

The community’s teacher, Mr. Kjonstad, took over services, and Rev. Stoppel from the Marburg German Mission presided over Holy Communion. St. John's in Shelley Beach, pastored by Rev. Toby Ahlers, is the remaining confessional Lutheran church in the area. Like all the SA Lutheran churches, it primarily serves the vestiges of German immigration, and they have a tough time filling the pews.

Pastor Berg was buried in the church cemetery after he died in Durban on November 6, 1912. There is no clear information about Cornelia’s death and burial, but it appears to have also been in Durban.

Johannesburg & Durban

One of Emil and Cornelia’s daughters, Alfa (the sixth of ten children, born in North Shields in February 1878), married Sverre Landmark, another Settler who hailed from Balestrand, Norway, where he was born in June 1870. My paternal grandmother, whose name was anglicized to Alpha, was born in October 1914 in Malvern, a working-class suburb close to the gold mines east of Johannesburg, where the family settled after the trek from Natal. At some point, the parents and some of the children returned to Durban.

Unusually for the era and place, my grandmother finished high school, which she attributed to her Norwegian parents insisting that all the children should be well educated to avoid the grind of manual labor they had experienced and witnessed. Those children were all fully assimilated South Africans. I never heard my grandmother speak Norwegian besides a few simple phrases, mostly tusen takk! Her spiritual life was chaotic, and she never talked about her Lutheran upbringing.

Alpha married my grandfather, Bramwell, in October 1936. They met in Durban, where he was washing windows (as a second job to supplement his lifeguard job on Durban’s beaches) at her employer’s business, where she was a bookkeeping clerk.

He was the son of Welsh-Cornish settlers who owned a quarry and stonemasonry business near Kroonstad (now Maokeng) in the Orange Free State. The large family was also famous in the area for its brass band performances as Salvation Army members. The family enterprise built many of the beautiful sandstone churches and bridges in the area that still stand today. That business failed during the Great Depression, and the family relocated to Johannesburg for work. The men/boys were employed as stonemasons for the Johannesburg Public Library, which opened in 1935 as a public works project.

In August 1982, the family traveled to Marburg to celebrate the centenary of the Settlers’ arrival. There were still enough families in the area to sustain a Lutheran congregation, and services were sometimes conducted in Norwegian. However, by the 1990s, the congregation ceased to be viable, Lutheran, or Norwegian.

The community never gained the critical mass required to grow and sustain itself because Norwegian immigration never resumed once the Second Boer War started6, instigated by the City of London so that it could steal the Transvaal’s gold.

The Boer Republic of Natalia was annexed by the British government on 4 May 1843 and renamed The Colony of Natal. On 31 May 1910, in the wake of the South African Civil War, it was combined with the two defeated Boer republics, Transvaal and Orange Free State, and the British-controlled Cape Colony to become the Union of South Africa. The province is now known as KwaZulu-Natal, reflecting the dominant Zulu tribe within its boundaries. At the time, other branches of the family had been in Cape Colony almost from its Dutch settlement, while the Welsh side of the family was in Kroonstad in the Orange Free State.

LOT 1: Rasmus Sandanger (builder), wife Helene. With Peter Knotten, wife Maren, child Anders.

LOT 2: Matias Holte (blacksmith), wife Karen, child Konrad. With Johan Myklebust and Ane Muren.

LOT 3: Isak Igesund (farmer), wife Dortea, child Anna. With Jakob and Olava Ribbestad.

LOT 4: Johan Nero, wife Karen, children Anna and Dorthea. With Martin Amundsen and Ane Sande.

LOT 6: Ole Valdal (tailor), wife Beate, children Marie, Lina, Olaf. With Regine Johnson and Severin Loken.

LOT 7: Kristian Rodseth (goldsmith), wife Kristine, children Aage, Anna, Marje, Elisabet. With Johanne Oie and Peder Ertesvaag.

LOT 8: John Kipperberg (seaman and fisherman), wife Gurine. With Emblem, wife Marit, children Trine, Lauritz.

LOT 9. Elling Pahr (teacher), wife Ane, children, Olava, Kristine, Pernille, Peder, Anna, Eilert and Ole. With A. Hansen.

LOT 10: John Lillebo (builder), wife Kanutte, children Peder, Anna, Pernille, Andreas. With Knut Myklebust and Jorgine Ensti.

LOT 11: K. O. Standal (painter), wife Johanne. K. E. Standal, wife Oline.

LOT 12: K. Martinsen (merchant), wife Elisabet, children Margrete, Klara, Elise, Martin. With Kaia and Gudve Rogne and E. Brudevik.

LOT 13: Ole Haajem (shipbuilder), wife Hendrikke, children Edvard, Anna, Laura, Karl, Ole, Nora. With Petrine, Hans and Nille Haajem.

LOT 14: Emil Berg (pastor), wife Cornelia, children Johan, Gusta, Marie, Magda, Alfa, Harald, Arthur. With Anna Brungot, J. Melsæter.

LOT 15: C. D. Lund (landscape gardener), wife Marie, children Sverre, Einar, Ragnhild, Astrid. With brother Tank Lund.

LOT 16: A. Andersen (bookseller), wife Gertrud, children Johanne, Hilma, Andreas, Karen. With Elias Rodseth, Ingebrigt, Edvard Bye, Marie Jorgensen and Vaernes.

LOT 17: Church and School Lot.

LOT 18: Peter Brune (boatbuilder), son Ole. With Marie Moe and R. Nederhus.

LOT 19: O. Vinjevold (farmer), wife Oline, children Oline, Peder, Oluffa, Anna, Josefine, Andreas. With Anders Stigen.

LOT 20: F. Hufft (weaver), wife Kristine, children Sofie, Inga. With Jorgen VoId and Gurine Frisvold.

LOT 23: Martinus Gidske (farmer), wife Anna, children Anna, Petter, Bernt, Berte. With Johan Petersen and Nikoline Londahl.

LOT 25: Gjert Kvalsvig, wife Marie, child Gustav. With J. Johannesen and Sevrine Paulsen.

LOT 29: Nils Oie, wife Malene, children John and Guttorm, Kannutte and Ingeborg and Kornelia. With O.J. Brauteseth and Karoline Haajem.

LOT 30: T. O. Dahle (mechanic & shoemaker), wife, children Anna, Gusta, Thea, Ludvig, Oluff, Kornelius. With Ingeborg Dyb, W. Andersen and Marie Dahle.

LOT 31: A. Birkelund (farmer), wife Marta, children Lars and Larsina. With Ane Vatne and Peder Dahle.

LOT 32: P. Haram (farmer), wife Cecilia, six children.

LOT 33: John Oie (farmer), wife Karen. With Olai Vatne and Malene Eidseth.

LOT 35: Borgensen (bookbinder), wife Marie, child Eivind. With Londahl, Wife Ragnhild, children Martha, DevoId and Dorthea.

LOT 36: Pettersen (farmer) and J. Andersen.

LOT 37: Knut Haggeselle (farmer), wife Johanne, children Sofie and Ida. With mother Maren and brother Anders, and Anna Karlsen.

LOT 41: F. Bodtker (carpenter), wife Cecelie, children Fritz, Paul, Marie, Rebekka. With L. Berntsen.

LOT 43: P. Trandal (baker), Haakon Hjelle and Elen Ekornes.

LOT 44: J. Kjonstad (farmer), child Dina. With Ingeborg Valum and Olaus Skjerve.

LOT 45: G. Kjonstad (teacher), wife Elise. With Dagna and Emil Holte. Zefanias Olsen. Grimstad, Karl Meeg and Lina Pettersen.

LOT 46: H. Andreasen (farmer) and Kristian Olsen.

LOT 50: E. Bjorseth (cabinet maker), wife Anne, children Anna, Peder, Alfred, Olivia. With Johan Vernes.

Cornelia’s last name is German rather than Dutch, so there are some assumptions about intermarriage or relocation by her family, for whom no firm records are available.

The Anglo-Egyptian War dominated London’s newspapers of the day.

Servants: Anna Brungot and J. Melsæter.

The war was costly, requiring 500,000 empire troops and £20 billion (2024 pounds) to defeat 88,000 men under arms from the Transvaal and Orange Free State Republics. Brutal British tactics, including concentration camps for women and children, burning farms and homes, and exiling captured men to St. Helena, created enduring friction between Afrikaner and English South Africans.