Amazon Has Reinvented the Consumer, but Ad Crucem Stays Safe

Amazon's greatest competitive achievements are not logistics, operational scale, data centers, and every product under the sun delivered to your door in hours - it's transforming the consumer.

Every retailer competes against Amazon whether they want to or not. Amazon has successfully hacked America’s disastrous global outsourcing and corporate consolidation fetish to wipe out competitors and set the pace and tone for consumer retailing. It has so successfully commodified a swathe of products that branding is irrelevant in many categories, with items sporting absurd names like “Agptek” or “Junnuj.” However, that’s nothing compared with its reinvention of the consumer, but Ad Crucem has a semi-secret weapon to fight back.

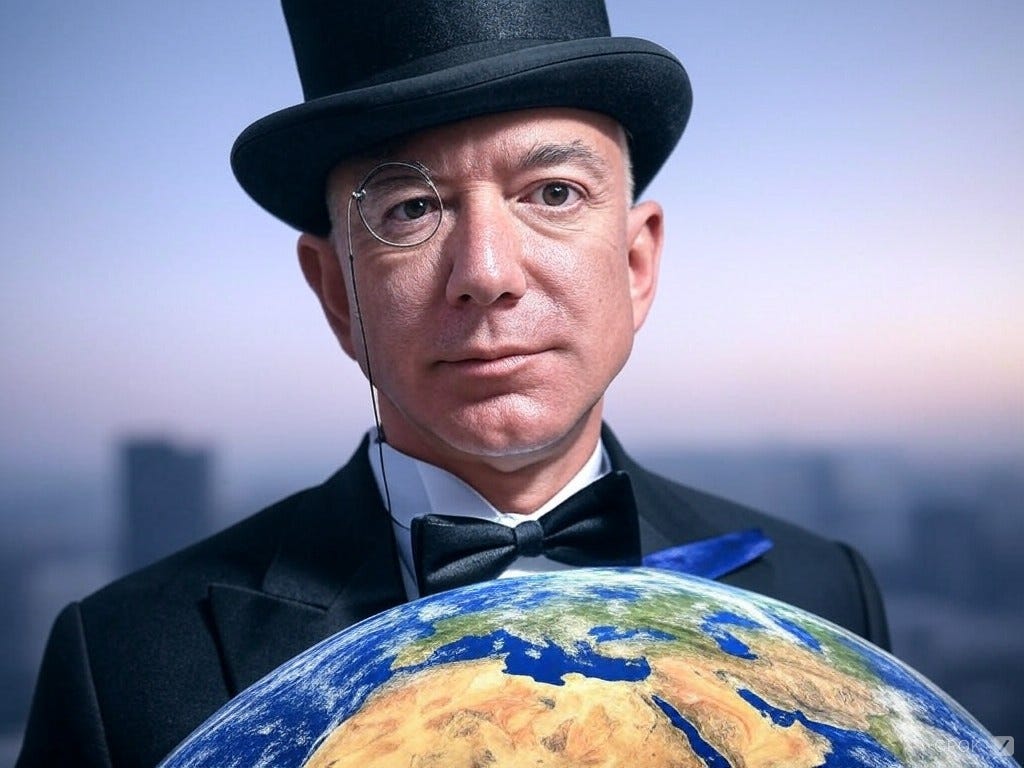

Amazon's achievements are impressive, if not revolutionary, primarily because Jeff Bezos beat all the naysayers who said the company would never achieve a return on investment following its start-up burn rate. However, if you bought its stock at the peak of the tech bubble in 1999 and held on to it, the appreciation is a nominal 11,500%. It has grown to be the US's fourth largest publicly traded company by market capitalization ($2.4 trillion), almost 2.5 times larger than Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, which has been in business much longer. Granted, Berkshire is a metronymic free cash flow juggernaut, but Amazon has crazy bursts like $70 billion in the trailing twelve months against BRK’s $21 billion.

Keep the Customer Home

Amazon has done to retail what Netflix did to movie theatres—it has kept the customer home and fostered loyalty through an internet connection it doesn’t even contribute to. The subsequent development was direct-to-consumer channels, where popular brands exist as their own “shops” with a direct pipeline to Amazon’s customers and piggybacking on its delivery systems, further disintermediating traditional retailers. Competition was further stimulated in every category by inviting anyone with a product to sell directly to Amazon’s billions of customers.1

The largest retailers have responded by trying to clone and replicate Amazon’s model. Still, they are significantly disadvantaged by not having the equivalent of Amazon Web Services, which can be thought of as a combination of Wal-Mart and Oracle.

The challenges are immense for small retailers because Amazon has fundamentally altered consumer expectations, attitudes, and behavior.

Return at Will

In South Africa, returns were unheard of. The operating principle was, “You bought it, you own it.” Consequently, shopping was time-consuming. Before going through checkout, you ensured that your shoes and clothes fit and were precisely what you wanted. Big ticket items were mulled over for weeks before opening a wallet.

As a result, product return culture was one of the most significant cultural shocks we experienced after immigrating. If you don’t like what you buy, return it months later, even after use!

Amazon has taken this to another level with its no-questions-asked returns policy. When we drop off Ad Crucem’s shipping at UPS, someone is always busy returning products to Amazon without even bothering to box them up.

It is exceptionally customer-friendly and makes Amazon much more competitive at the expense of small retailers because that return policy has become the market norm. That’s how modern capitalism is incentivized to function. Still, it reinforces that Amazon has probably become a “too-big-to-fail” retail monopoly - because it is so critical to the national supply chain and controls a massive chunk of the data flowing across global networks.

Returns are not “free”—they are built into the price of every product because the seller ultimately pays to restock (time-consuming labor to inspect, count, wrap, and return to inventory) or has to discard damaged returns. This is a considerable risk for Ad Crucem, as we deliberately operate with low margins because we aim to serve the church rather than drive new German cars parked at a weekend lake house.

Customers are King & Queen

Fortunately, the overall rise in impulse purchasing with limited research has not impacted Ad Crucem as much as it could have because we have something Amazon does not—a core Christian customer base. There is a marked difference in dealing with Christian consumers, and the narrow focus on Confessional Lutherans who understand and want our products makes it that much easier.

Ad Crucem’s return rates, for any reason, are exceptionally low, and we believe it is because the customers understand what we are attempting to accomplish with the business, in addition to having products that meet needs and satisfy purchasing power.

Ad Crucem’s customers are unusual for the breadth of unsolicited brand ambassadorship they provide. For example, one customer recently received an item intended for someone else because of our shipping mistake. He mailed the item to its correct destination at his own initiative and cost without expecting reimbursement or reward. If we inadvertently package extra items in a shipment, we know about it because customers ask how to return the additional items.

It typifies our customer interchanges, which can be described as dealing with an extended fraternal partnership rather than impersonal stranger engagements haggling over money. The positive interactions are worth tens of thousands of dollars in equivalent marketing that can instead be diverted to maintaining low margins, sourcing American materials, producing products in-house, and investing in new equipment and capacity. It’s a high-trust arrangement that benefits everyone, and one day, we hope it returns to being the norm rather than the exception for all retailing.

Thanks to you, Ad Crucem will never be Amazon, and that’s how it should be, dear partners and friends.

I was just thinking Berkshire Hathaway is sitting on about 270+ billion dollars of cash reserves, at the moment, and has added Domino's Pizza to their portfolio as well, two really different entities for sure.