Gain-of-Function Theology: A Discussion With The CloudCast

How Theological Novelty Functions Like Gain-of-Function Research, Taking Small Errors and Amplifying Them Until They Overwhelm the Host Institution

Introductory Summary

In this meandering and candid conversation with Pr. Josh Reber and Pr. David Buchs, Tim reflects on his background in journalism, public policy, publishing, and general business, tracing how investigative instincts formed in South Africa’s political and financial transitions now inform his work in church-focused commentary and critique. Drawing on experiences with corporate corruption, media capture, and institutional failure, Wood argues that the most dangerous forms of corruption are not financial but doctrinal, subtle, incremental compromises that hollow out institutions long before collapse becomes visible.

The discussion turns to the Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod (LCMS), examining how theological drift, conflict avoidance, and failures of ecclesiastical supervision have weakened preaching, discipline, and trust. Wood critiques “gospel reductionism,” the collapse of sanctification into a mechanical view of justification, and a culture that soothes consciences rather than forms them. He connects these theological patterns to concrete institutional outcomes: declining attendance, uneven discipline (especially around the Sixth Commandment), and governance structures that emphasize administration over doctrinal responsibility.

Using the Southeastern District controversy as a case study, Wood and the hosts explore how breakdowns in oversight can lead to the mistreatment of faithful laity and the protection of institutional reputations at the expense of truth. The conversation concludes with a call for serious self-examination, clearer governance, sharper preaching, and renewed courage among church leaders, grounded in the conviction that fidelity to Scripture, not cultural accommodation or procedural nicety, is the only foundation on which the Church can endure.

Transcript

Note: this is a machine translation.

HOST: This is great. Let me introduce you a little bit—and correct me if I’m wrong. I’m doing this from memory, based on what I know about you. You’re the owner-operator of Ad Crucem, a business in the Denver area, and you guys do liturgical and Christian art. I was just looking at your website—looks great. So thanks for doing that. You’re a member and the chairman of Trinity Lutheran in Denver, Colorado, and you sit on the Board of Regents at Concordia Seminary in St. Louis. You got any time to do anything else?

WOOD: One correction: as of December 31, the Lord has released me from my obligations to Trinity Lutheran. So I’m now just a pew-sitter with no responsibilities, and I’m kind of looking forward to it after eight years.

HOST: Hey, that’s good. I always joke with my members that it’s much easier to get somebody on the roof of the church than in the pews.

WOOD: Not untrue, right? Yeah. So those are the core things. I do have a day job in the secular world, but it’s irrelevant to what we’re discussing today. What might be relevant, though, is that I do have a background in journalism.

HOST: Yeah—so you have a background in journalism, don’t you?

WOOD: Yes. I’ll try to make a long story short. I started work as a public policy analyst straight out of university and worked for an organization helping them transition from the old South African government to the new South African government. So I was kind of the CEO’s lackey—wrote speeches. We did a lot of work in parliament. It was obviously a huge transition around 1994, which is when I started working.

Through that I became interested in the internet and put in one of the first corporate websites in all of Africa. It helped to have the boss—the main boss—right next door to you. He let me run with these things. Through that I developed an interest in publishing systems, content, and took a job at the then largest weekly-circulation newspaper in South Africa, the Sunday Times, to help them start their first internet edition.

In the course of doing the technical work to get all of that up and running, I saw an opportunity to do some writing. So I kind of fell into journalism on the financial-markets side—capital markets—as a parallel piece of that transition.

HOST: Wow. Tim, you wrote a couple of articles on your Substack about some of those experiences, as well as reporting on corruption. How does that transition take place—from enjoying writing when you see the opportunity to now doing some investigative journalism?

WOOD: Yeah, you know, I think it became clear to readers that I was never going to back off from a controversial story. So I would touch topics that other journalists would hesitate on, because there was always a bit of corporate capture. In financial journalism, there’s always the risk that the CEO is going to call and say, “We’re pulling our advertising.” Then the editor and publisher and board go crazy because you’re costing them money.

Well, I just didn’t care, and I published what needed to be published. I took a lot of flak from companies who weren’t used to being criticized in public. That was very focused on the tech industry in South Africa, which was booming at the time.

As a result, I started to get a trickle of stories that were really significant. The big one was that I became aware of a visit by North Koreans to South Africa’s nuclear facilities, facilitated by the ANC government, where they appear to have departed with nuclear materials and/or nuclear secrets. That story didn’t get a ton of traction, but it appears to have caught the attention of certain—shall we say—agencies.

HOST: So when you get more flak on a story, is that kind of a sign that it’s a bigger story and you need to go deeper?

WOOD: Yeah. The old saying is: you get more flak when you’re over the target. And that’s generally true. Sometimes it’s because you’re just wrong, and journalists have to be very careful—because once you get into this world, people start feeding you stories they want to see published because it benefits them.

For example, I would get tips from hedge funds because they were shorting a particular stock and wanted a particular outcome. Or I would get positive tips. And the key distinction is: during all my time as a financial journalist, I never once took an inducement—whereas I know full well that a lot of my colleagues were being given free shares, options, warrants, which tainted their writing. I refused all of that. I could have become very rich, but you absolutely sell your soul.

When you’re chasing a big story, it was easier when I was younger because there was nothing to lose, right? We broke the Oil-for-Food scandal with the United Nations, where Saddam Hussein was selling oil, but the UN was essentially facilitating it. There wasn’t a barrel of oil Saddam was selling that wasn’t known by the UN, and also the United States. I only came to understand that part later. But this was a massive intelligence-network operation to skim profits from Iraqi oil.

The purpose was not no-fly zones and inserting democracy. It was about reaping massive—tens of billions of dollars—siphoned out of the program under the guise of sanctions and keeping a lid on him.

Those things also come with danger. But I was young. We had a young family. We moved to America with a one-year-old and three suitcases. So what were they going to do? But they did tap our phones. There was a lot of mysterious stuff going on. I don’t think my wife knows all of it, which is probably just as well—new babies in the house and it’s not the sort of thing a wife wants.

Then in the corporate world, where I broke a big story, I didn’t publish it immediately. I sent it to the company beforehand to say, “Look, this is what I’ve uncovered. Is what I’m saying fair?” On Monday morning, I didn’t get a call to say yes or no. I got a lawyer’s letter threatening to sue me into oblivion. So I published the letter—and the stock was down 25% within two minutes, because the market was aware that something was being hidden.

Those are all experiences that prepared you for what we’re doing now, which was also incidental. Ad Crucem News was started because we were really struggling to break into new markets. Existing advertising wasn’t working. So I thought: why don’t we create our own market? Let’s find the customers ourselves by doing something I know how to do. That turned out to be very successful. And part of that was shining a light on the good and the bad of what’s going on in our synod.

HOST: That raises a question I’ve been pondering. I’ve been thinking about the nature of corruption in the financial industry or the business world—there’s always a trade of power or money for favor, for an advantage. And I was thinking about how that’s different in the church.

On the one hand, it’s kind of easy—if you find out somebody’s been siphoning off cash, there’s a trail you can follow and clear culpability. But it seems like the kind of corruption that can infect the church is of a different character, and tracing it is much more challenging. Maybe you can comment on that.

WOOD: Yeah, that’s perceptive. In business, corruption is pretty clear. It’s easy to see where the path of inducement lies. There’s the old saying: if you want to corrupt a Brit, you show him little boys; if you want to corrupt a Frenchman, you show him little girls; if you want to corrupt an American, you show him money. These things are generally true, unfortunately.

Now how does that look in the church? I think it’s combinations of those things. But the greatest risk is that you become corrupt in your doctrine. The corruption in life is going to follow that, but it’s so difficult to perceive when your doctrine is under attack because it’s not always a conspiracy or systematic.

How do these things creep in and cause us to change our view on Scripture? That’s the real basis. Take contraception. It was accepted that contraception was prohibited in the church in the same way usury was prohibited. Yet over time we reached a point where the Missouri Synod’s senior theological entity said it’s no big deal—go ahead if you want to use contraception.

How do these things develop? It’s never someone throwing a flash-bang grenade into the chancel and saying, “Today we are doing this, and yesterday is old.” These are tiny seeds that Satan plants, and they metastasize over decades and decades—if not centuries—until we find ourselves in a position where we reflect society and the culture more than we do the Bible.

That’s where the incipient corruption is. The ELCA and other mainline churches didn’t get to where they were overnight. It was a progressive process.

HOST: Mhm.

WOOD: And in each case, there was a point of compromise by an individual who came out of seminary probably as enthusiastic and full of zeal as anyone, and yet somehow they were compromised and put in a position where they said, “Yeah, we can go along with this.”

HOST: Tracing that historically—do you think, in our current moment, a lot of it comes out of 19th-century Germany in particular?

WOOD: Tthis is where it’s not my expertise, but principally from reading and listening to Dr. David Scaer—he’s been warning, as did Hermann Otten, for decades. Dr. Scaer has been teaching for half a century, and right at the start of his teaching at the seminary—and even as a pastor—he was warning that a new theology was being introduced into the Missouri Synod, and that theology was a variant of Barthianism that underwent a kind of gain-of-function amplification at Valparaiso University. And unfortunately, Fort Wayne was kind of the endowed chair of that gain-of-function continued amplification.

So yes: sourced from 19th-century Germany, imported into the United States, and then cultivated.

I don’t understand all the nuances. I don’t have a full grasp of the history, but I do wish our best minds would look at that path and know where it should have been cut off—so we learn again.

And part of this is: we’re very triumphant about the “Battle for the Bible.” Did we actually win it? Part of the problem there is that friends/enemies distinction. We needed scorched earth. Everyone who subscribed to even the least part of higher critical theory and wasn’t on board with the needed changes needed to go—because it wasn’t just at the seminary. It had already spread into the parishes.

You can see it in the laity catechized through the ’50s, ’60s, and early ’70s. They’re still alive today and they have a very different mindset than what you would expect Lutherans to believe, teach, and confess.

So clearly, that theology from the ’40s was starting to be propagated, it made its way throughout the synod in various forms, and it needed to be crushed—and we lacked the will to crush it.

HOST: That raises a question for me. Oh—go ahead, Josh.

JOSH: I was going to say, I have two follow-up questions. First, have you identified—by comparison—who Anthony Fauci is for American Lutheranism?

WOOD: That could be very dangerous!

But you know, we can look at the Bad Boll conferences as one means of transmission—where our guys seem to be so enamored of these German theologians and their wisdom and depth of insight. And you know what it’s like with eggheads, right? That’s why they have these crazy titles on their academic papers—they’re competing to have the most ludicrous-sounding thing that apparently is impressive, and they’re always in search of how to be completely unique in what they present for their thesis.

That’s very dangerous in theology. They started dancing on the head of a pin, and lo and behold, you see that transmission into the United States.

And the Barthianism—you can see it in Forde; you can see it in Paulson. I don’t think Elert could be accused of doing it intentionally, but it was a consequence of some of the things he was teaching that we picked up and developed—especially with Forde—that we can collapse the law and gospel distinction: law becomes the enemy.

And the Barthian side is: Scripture only exists insofar as the gospel is holding it. So there’s confusion about what Scripture is. And we go into this radical gospel reductionism that has steamrolled everything.

Its most defective expression is in the ELCA, but there are forms of it through the ELS, WELS, and our own synod. And where I would pinpoint it is: it has become more important for Missourians to articulate the doctrine of justification than to believe it.

A senior teacher of the church said to me this week, “Missouri was crucified on the doctrine of justification.” That’s a radical thing to say, because we lost sight of the atonement. And these reductionists have purposefully muddied the water on the doctrine of atonement, which is really the main thing. But we’ve turned it into justification and made it very mechanical: you’re a good Lutheran if you can explain justification, and then you wash your hands of it.

Once you’ve been catechized, off you go—life is great, you’ve got the golden ticket to heaven, that’s all that’s needed. Sanctification disappears. Never mind the third use of the law. We become entirely passive.

So we take the doctrine of justification and transpose it onto sanctification and say, “Well, I’m just the passive actor. God will give me the works I need to do, and if I’m conscious about doing good works then I’m trying to self-justify.” So it becomes a strange exercise in opposing yourself: if you dare to think you’re doing something worthwhile, just know you’re trying to scale the ladder of heaven and break down the doors.

It is existentially annihilating if you follow it to its conclusion.

HOST: The alignment of incentives is so interesting to me because, on the one hand, you have—like you described—this pursuit of novelty among academics. And for pastors, there’s something about being the guy who can say it in the cleverest way that turns a light bulb on for people: “Oh, now I finally get what I’ve been wrestling with.”

But it’s not actually a resolution. It’s not repentance and faith and good works. It’s the eraser of the problem—it does away with it.

And what you’ve articulated—for Missouri being the doctrine of justification—the parallel for me is in the Old Testament with the priests who say “peace, peace” when there is no peace. They’re not quoting Article IV, but they’re pointing at the temple and the priests and sacrifices, saying, “Look, don’t you see? This means you don’t have to worry anymore.” And I’m sure people who were neither qualified to adjudicate that—or who didn’t want to do the hard work—were all too pleased to hear that message.

WOOD: Yeah. It’s very soothing. When we converted out of Fundamentalism, our first contact with Lutheranism was through the radical side. And it’s very intoxicating to come from a law-heavy, prescriptive background to hear that you have to do nothing—and that when pastors are throwing verbs at you, they are the wolves.

It took us a couple years to break out of that. One of the first books we received was the Heidelberg Disputation. Catnip, man! For a fundamentalist, this is glorious. But it’s like smearing Vaseline on your glasses.

So you’ve exited one circus and gone into another circus. Whereas Lutheran theology—look, I like to mock the guys with “our great Lutheran theology, trademark”. It’s the whole counsel of God. It’s not a formula we write down so we can express ourselves.

Your authentic Lutheran self is the one that can hammer out the Ten Commandments, doctrine of justification—but also: what does it mean to live in this life before we die? Should we not fear hell? Actually: have a very healthy, morbid fear of going to hell. And how do we address that? We stay in the Word. We stay with the sacraments, which fortify us.

But there’s a life to live as a Christian, which St. Paul sets out. Galatians is really clear. People take Galatians as “see, the law is bad,” but he’s addressing a particular thing and saying: get the balance right. Now go and do good things and stop with the nonsense.

HOST: Yeah—he says, “Put the works of the flesh to death” at the conclusion of his epistle, right? And then “walk according to the Spirit.” So the whole point is to live a good Christian life.

It’s self-defeating to say, “This is what God has done for you—and by the way, none of the rest of it matters.”

What does it mean to put our flesh under subjection? What does it mean that your flesh is deliberately going to go to war with your soul—because it carries this residue, this echo of your unregenerate self that is determined to drag you to hell?

So we need to be conscious. We have to get away from this hyper-monergistic thing that says, “Hey kids, you’re fine—as long as you were baptized and catechized.” And that’s why I cringe a little when people say, “Oh, remember your baptism.” What are they actually communicating?

What they’re often communicating is what you hear from the pulpit 80% of the time in Missouri: “Hey, we’re all bad. You’re terrible. I’m terrible. But Jesus died to redeem that.” These propositions are true. But the way it gets heard is: it doesn’t matter what your life looks like. Sanctification has no bearing on salvation. That’s incredibly dangerous.

And then you have this parallel development where the laity have been catechized to listen for the division of law and gospel. So the focus of how they respond to the pastor is: “You gave me 51% law and 49% gospel—and you finished with the law, not the gospel, so I’m reporting you to the district president and we’re sending you to seminary for rehab.”

HOST: The responsibility of pastors in all this stands out clearly to me. I was trying to look up a passage from Ecclesiastes about how when the evildoer is not promptly punished, the wicked rejoice and have their heyday—something to that effect. You could apply that in society, in disciplining your kids, but also to the old man: he needs to be swiftly and decisively put to death—crucified.

And that’s the responsibility of preachers—to deliver that message. What’s harrowing is we’ve cultivated an attitude among people where their ears are used to being itched—scratched. To hear God’s Word without qualifications, without an “exit ramp,” is jarring.

It’s like preaching on the divorce texts and saying, “Whoever divorces his wife and marries another commits adultery.” Full stop. That’s where it ends. There’s no exit ramp. It’s just how it is.

Until we get good at saying those things, the flesh of our hearers goes on enjoying its heyday, right?

WOOD: It’s very easy for us to take great comfort when the flesh is affirmed. Divorce is incredibly hard. I recently wrote about clergy divorce and it was astonishing what came out of that.

The main takeaway was that ecclesial supervision assumes a pastor deserves “extra grace” if he’s not at fault. Well, that’s not in the Bible. The Bible doesn’t say you get wife number two, three, four, five, six because the previous wives were scoundrels. It says you’re a husband of one wife.

The burden on pastors is enormous. Most pastors understand that when you receive the call, it’s the first twist of the thumb screw. Then ordination tightens the thumb screw five or six times, because now you are living under a standard I do not have to live under.

And it seems the bishops want to loosen the thumb screws—not because they’re punishing men, but because that thumb screw alerts the conscience: be careful. The prowling lion is around the corner and he wants to devour you and destroy your ministry, and then weaken the resolve of your parishioners.

A parishioner loves nothing more than a fallen pastor who remains in place. There’s no way you can discipline a parishioner like that because they’ll turn around and say, “Aha—but you’re divorced, or you did this, or you did that, so who are you to tell me to clean up my life?”

HOST: Yeah—that’s exactly the problem in Malachi chapter 2. The clergy were leaving their wives, and then that resulted in the Israelites doing it, and the priest couldn’t say anything because he was doing the same thing.

So I’m with you. We need to clean up our clergy roster. I don’t necessarily mean eliminate guys, but the buck stops with us.

WOOD: Yeah—it absolutely does. But it stops first with the men who have accepted to be the teachers of the church: circuit visitors, district presidents, senior vice presidents, and the synod president. They have agreed to be the chief theological officers. Constitutionally, they signed on the bottom line that their primary work is to maintain pure doctrine—not worry about the district bank balance, not have the best logo for the convention, not have great badges where all the spelling is correct.

Doctrine, doctrine, doctrine. The other stuff comes much later.

HOST: Well, you would think if that was their goal, they could come up with better anagrams.

The Holy Spirit doesn’t promise that as a gift along the way!

HOST: This raises practical questions for me. When Pastor Reber and I were together in St. Cloud before I headed south, we thought a lot about what kind of work we could do at our district convention to do something productive—bring resolutions that would actually be effective.

Some of the things we did were to bring these kinds of questions to the fore—to simply say what Scripture says as a resolved statement. Divorce is an abomination. That kind of thing.

And I’m thinking about ecclesiastical supervision, and how heartening it is for someone who bears authority to receive a mandate to do the work they’ve been asked to do. So here’s my current thought: what if we sent a resolution to the district convention instructing the district president to remove men from office who are divorced? Would that accomplish anything? It certainly wouldn’t pass, but would it be useful?

WOOD: In a sense it’s redundant, right? The district president has already agreed to do that. We can argue edge cases. I’ve got no problem with a man abandoned by his wife remaining in the ministry if he doesn’t get married [again].

But we have many instances where there are pastors with not just two wives, but three or four wives. How does that stand? How can that be justified? It clearly can’t.

So there’s a deficiency of supervision, which communicates to everyone that the nature of the office is mostly for civil control and comity—not doctrinal supervision. There’s intense conflict avoidance. Part of that is cultural. Missouri is dominated by German descendants. Germans by nature are conflict-avoidant. You’re clustered in the Midwest. Strong cultural patterns of behavior have surfaced into the offices. Our men have been unable to set aside those cultural impulses and do what is required.

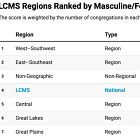

Even if you do it on a constitutional basis—never mind opening Scripture and saying what does this do—our constitutions are incredibly clear: the duty is to maintain pure doctrine. And yet synod president after synod president has allowed these things to fray in all the districts to one extent or another. Some are much worse. There’s a strong correlation with where they’re situated. The saltwater districts are like they are because the saltwater states have peculiar cultural norms.

HOST: I keep hearing on a lot of podcasts that the synod is strictly advisory—only there to advise. I keep thinking: what’s the point of a synod if there’s no supervision?

WOOD: That’s not what the constitutions say. They’re not just advisory. They very clearly have supervisory mandates built into them. Now, they’re tilted toward the administrative side rather than the doctrinal side, but throughout our constitutions and bylaws—from parish level up to synod—there are strong supervisory directives and consequences when supervision fails or is ignored.

I think the handwaving about being “advisory” is because certain factions are preparing to exit the synod, and the excuse will be: you’ve gone from being advisory to overstepping your mark, interfering in our congregational life.

HOST: Yeah. Let’s put some concrete meat on this and start talking about the controversy of the Southeastern District, because I think all these things come together with what’s happened there in the last year. Can you give us the basic timeline and facts of what happened in Virginia?

WOOD: Yeah. It’s a tragic situation. We had no desire to publish the initial story. We went out of our way to give all parties the opportunity to pull the handbrake. The initial report was distributed to everyone—ecclesial supervisors—starting with my pastor and my district president. I left it there. I gave my district president the option to tell the senior vice president and President Harrison. My recommendation was that he did. Whether he did or didn’t, I don’t know.

My expectation was we were going to get a call to say, “Would you mind holding the story because XYZ is happening?” I would gladly have left it in draft.

To rewind: the reason it got published is because there was a complete collapse of supervision—an abandonment of the office at multiple levels. And what drove us to consider publishing is that the complainants were devoured. They were not devoured by the world. They were devoured by men who took oaths of office, had hands laid on them, and promised to feed the sheep—but they didn’t. They jumped out of the pulpit and started tearing these people apart. They were horrendously abused.

I don’t think people understand the extent to which these lay men and women were torn apart—had their flesh shipped around like a certain rabbi in Judges who spread his concubine about. Zero care.

And it’s actually a much longer timeline than just a year, but essentially for almost a year the complainants had gone to their pastor and church leadership and said: we are really concerned about homosexual affinity in the congregation; Islamic propaganda in the school library; first graders attending a queer musical; and a host of other problems.

This wasn’t “oopsies.” If I make an analogy: it’s like we discover a church has an affinity for bank robbery, there are burglary tools lying around, the pastor has a mask and gloves on his desk, his bookshelf is filled with safecracking tutorials, and the church is flush every couple months. There’s a pattern of behavior where we can say: this church is strongly aligned with bank robbing and needs to be dealt with.

In this case, the congregation exhibited a long-standing pattern of homosexual affiliation, transgender affiliation, and submission to multiculturalism. When these people brought specific examples, the response was to do that thing pastors aren’t allowed to do—be authoritarian. There was a crackdown where they tried to remove these individuals from voting membership and participation in the life of the church without even excommunicating them.

They were so cowardly they couldn’t bring them before the church and say: this is what you’ve done to oppose God, and why we must prevent you from taking the Lord’s Supper. No—they just said: don’t step foot across the threshold, because we don’t like what you’re saying about us.

The district president was given all the information—President Harmon—and lickety-split he was ready to sign off and say: no problem here. President Harrison was aware at that time as well. He clearly didn’t want to get involved—it’s unpleasant. But it got worse.

The [complainants] who were righteously—not self-righteously—saying: this church opposes the clear instruction of Scripture; please help us because we are being targeted—the response was to send in more wolves to take them out.

So our responsibility was not to launder the dirty washing in public. It was first to protect these sheep and get them justice.

Ultimately, they were vindicated. The story forced President Harrison to respond—even though he was misleading in saying it was being dealt with. It wasn’t. Eventually we got to the point where a pastor resigned with reluctance, and the district president affirmed the church and told them how horrible we are and how terrible it is that any of this came to light.

HOST: Has there been any substantive defense made in response to your publications—or the charges brought by the complainants?

WOOD: The only attempted defense was by Pastor Matt Barroso in the Atlantic District—one of the bigwigs on ALPB, American Lutheran Publicity Bureau—who indirectly, and I can’t say for certain, but it looked like an attempt to respond to us by saying: you guys are just being mean; you’re the schoolyard bullies. He used the phrase: “You have to come to terms with the new realities.”

What are these new realities? So it’s a partial defense.

Some commenters were clearer than the pastors. Pastor Benke, for example, came out with conspiracy theories—that we were in cahoots with someone and the design was to take out key voting blocks. Crazy stuff. But to this day, I’ve asked him multiple times to give a clear defense of what went on in that congregation and he refuses—yet remains very critical of what we did.

And it comes back to the problem where justification has become this label we slap on everything. Why call anyone out for sin? Look, they’ve been saved. Jesus said, “Everyone is a sinner.” So who are you to say these people are more or less sinful? That was never our point. The point is: when someone proudly stands up and says, “Look at my sin. Look how special it is. God loves this,” we have a huge problem.

There shouldn’t be excuses. Let’s deal with it in a loving way, but a firm way, because the consequence is people will go to hell—affirmed in the belief they were “born this way” and the highest love is to say: it’s just your DNA.

HOST: It seems like we’re willing publicly to call out certain sins. The counterexample: somebody comes out as a white nationalist and is spewing racist stuff—you can call that out the next day and call for excommunication.

So why can we call out certain sins and not others? Is it fear of the culture, or lawsuits? Is that part of the calculation?

WOOD: I think all those factors are in play. A transgender stole is not going to get national media attention, but a “white nationalist” will. So there’s a desire to deflect attention.

But at the end of the day, we only have 500,000 people in the pews on any given Sunday. We are completely irrelevant to American culture and politics. So why be afraid?

Still, there are incentives to allow the culture to dictate what we’re harsh with and what we let slide. And generally there appears to be a particular problem with the Sixth Commandment in the LCMS. This has been a long-standing issue. The Eilers transition issue put the synod into a tailspin years ago. Surely that should have been in the back of everyone’s mind: “Okay, we addressed this and we understand the issue.” And it’s not about being extra compassionate. It’s about being truthful—truthful about what the Bible demands we be truthful about.

And yet we don’t learn those lessons. We’re soft on Sixth Commandment issues in a way we would never be if we had proud bank robbers. The synod needs to ask itself hard questions: what happened that caused us to have a squishy view of the Sixth Commandment?

HOST: I’m thinking about discipline at the district level or circuit level—congregations, pastors. It begins within congregations and within homes, which is why all this is connected. The Pauline mandate for a pastor to manage his household well is necessary, because unless you know what it is to discipline your own children and care about their salvation, how could you ever discipline anyone else?

That indicates to me a ground-level reformation is needed: lots of people taking these matters seriously in their homes and personal lives, and pastors preaching accordingly.

Besides your efforts to publicize things, are there other things Christians—members of the Missouri Synod, pastors—should be doing to right the course of this ship?

WOOD: The priority task for the next 25 years is to find out why, for the last 25 years, our weekly attendance has halved but pastors per congregation as a ratio has increased 10%.

In any other sphere of life—medicine, engineering, business, aviation—if you were losing 50% of your customers, there would be a bloodbath at the top. You would retrain everyone to find out what happened.

We have to get serious! Put your finger on what happened that caused people to leave. Don’t blame the birth rate. We’re talking about the children of parents who walked away. Those parents are still in the congregation; their children have walked away in their millions. Not tens, not hundreds—millions. If we go back to 1945, we’re talking millions of people who said: I’m giving up on Missouri. Why? What happened spiritually that caused this exodus?

Yes, there’s a demographic component, but this is not just demographic decline. It’s primarily spiritual decline with a demographic tailwind.

From circuit level to district level to regional level to national conventions, we should only have resolutions that say: we want to put our finger on the precise problem that caused our people to stop believing the Bible—because we should be honest enough to say that.

I pray Missourians will stop just smiling at each other. It doesn’t mean we have to be unpleasant, but say true things. That doesn’t mean you hate the other person or wish the institution ill. But painting “all is well” is false. The outlook for the next 25 years is bleak, and what happens in the next quarter century will determine whether the LCMS survives in any form whatsoever.

There will always be a remnant. I’d prefer not just to be a remnant, but to make something people can live in—believe again, truly love the Bible again, apply it to their lives—and not be so casual that for a lot of people Sunday is just a nice club.

Those are harsh things. Maybe some of it is not true—then tell me. Bounce back. Let’s have these conversations. I don’t have the theological depth to unpack everything, but I do have the business sense to look at everything dispassionately and say: if this is a corporation I’m running, I’m pulling all the fire alarms and not sending happy memos saying the world is good and we just need to be more Book of Concord.

The analogy is like people who say, “If everyone just had a pocket constitution from Hillsdale College, America would heal.” If everyone just had a little pocket Book of Concord and read harder, all will be well. No, it won’t. Something more fundamental is going on that our pastors and teachers have to get to grips with.

HOST: So from that business and political side, the analogy I’m getting is: conventions are like the legislative branch and elected officials are like the executive branch. So what kind of resolutions can and should we pass, and how does the convention hold our executives to account?

WOOD: It’s tough because conventions are often window dressing. We say a lot. We formalize a lot. We’re good at Robert’s Rules of Order. We’ve got gifted parliamentarians, gifted guys at the podium, sleepy people in the crowd. A couple engaged guys who like to call the question. It’s a bit of a game.

What comes out of conventions often seems like reaffirmation of history. Lots of back-slapping. Sing the doxology. Comfort dogs are going to wear collars next year. Crazy stuff.

But they have a purpose. Good resolutions bind the office. An example where the office was not correctly bound is the Large Catechism annotated edition. There was never a resolution that funded it. Someone decided to load it with rocket fuel without guidelines issued by the convention. If you look at the resolutions, nobody gave permission to produce it. It said “explore.” “Explore” is very different from hiring authors, getting binding done, and distributing a finished product.

So it’s sloppiness. When we’re spending money, we must get more control and discipline. And overall we need to relook at governance where it’s not enough to say we proceed on Christian trust.

We’ve seen so many failures that we need a governance process that shifts from “you’re expected to do something” to “there is a duty to put measures in place that prevent bad things from happening.”

In business, it used to be: I’m responsible for ensuring audits are done and auditors find fraud. That world is changing. Now I have a fiduciary duty to put measures in place that prevent fraud. It’s not enough to look for it. There have to be active measures.

We’ve reached a point where it must be “trust but verify,” because the trust has been broken at almost every level. Let’s help ourselves by removing temptation and asking: what can we do in constitutions and bylaws at every level that creates a duty to prevent?

If someone doesn’t want to be a district president who has to make hard decisions, then don’t do it. We need to remove the idea that district presidency is a sinecure you get because you’ve served your time and now we boost your salary and benefits as you age out—like government workers.

There needs to be a top-to-bottom revision in governance with a focus on maintaining pure doctrine. Not because we’re policing people, but because without pure doctrine, you’ve built your house on sand. Fundamental.

And pure doctrine goes back to: if we say we’re people of the plain-spoken Word and we believe everything the Bible says—please, can we do that?

HOST: Who can argue with that appeal?

HOST: Hey, I want to thank you. In one of your articles—I don’t know if you knew this—you essentially told me I was the manliest man in the whole Missouri Synod. Because you said Minnesota North was the manliest district, and I’m the circuit visitor of the St. Cloud Circuit, which is the manliest circuit in the district. So on behalf of myself, thank you.

WOOD: Well, it’s our pleasure. That article was actually the most controversial. I was surprised how negatively people reacted. I don’t know if it’s the idea that we’re such blank slates that there are no masculine and feminine differences. I made no moral judgment about which was better. I simply said I’m interested in how people communicate.

If the Nebraska District is very feminine in how it showed in its convention materials, how on earth is it going to talk to Minnesota North and come to some agreement? Even before we get to biblical fidelity, if we have such different approaches to how we speak, you’re never going to be on the same page. That’s the concern.

I do have another binary, but I don’t know if I should publish it. People would lose their minds, and I don’t know if there are enough psych wards in the country to handle it.

HOST: Hey, I’ll publish it! You don’t have to publish it at Ad Crucem. You just send it to me. I’ll gladly do it.

HOST: This has been great. I really appreciate your time, Tim. I think I can speak for both of us: we appreciate your insight and the effort you’re making—both in your journalistic work and the work of Ad Crucem. Clearly the church is enjoying a lot of high-quality liturgical art because of your efforts, and we see the fruit of that.

WOOD: Yeah. Thank you. It’s a small effort. I’m a problem solver. As much as I criticize, I try to balance it by providing solutions.

When I criticized governments, I proposed a full package to revise governance. When I criticized pastoral formation, I provided a plan I think is workable—how we can reframe pastoral formation, vicarage programs, set up teaching churches as centers of excellence.

We hated the lack of historic Christian art. So, Wanita and I had to provide the solution. Can it fill the whole solution? No. We don’t have CPH’s $80 million balance sheet. But in our small way we’re making a dent—helping get us back to recognizing that art plays a role in communicating law and gospel.

That child who loses attention during the sermon might look at a banner and see the Agnus Dei and the blood flowing into the chalice—“Wow, I wonder what that means.” They see the chalice on the altar. The liturgy, hymnody—it’s all preaching. The art should preach too—part of the surrounding package that reinforces the pastor’s work. The preached Word is 90% of everything we need. If we can add one or two percent to help it go forward, then let’s do that.

HOST: Hey, I’ve got a book recommendation and then a second thing. Have you ever read The God Who Was There by Francis Schaeffer?

WOOD: I haven’t. I’ve skimmed it, but it’s always been recommended and I haven’t gotten to it.

HOST: Oh—what are you waiting for? It’s so good! You brought up art, and what he does is trace the development: it starts with philosophy, then trickles through art, then ends up in theology. It helps explain how we as an American culture ended up where we are, which I think is the big story of Missouri as well.

And the second thing: you talked about not knowing the theological development. I’d be happy to write some articles for Ad Crucem on the theological history of how we ended up where we are—if you’d be open to that.

WOOD: Yeah, we’re very open. We’ll publish almost anything as long as it’s not false doctrine. We’re happy to be a clearinghouse and publish material from a lot of people.

The more voices—and more expert theological voices—the better. I’m always hesitant to do too much theologically because I respect what the office is there for. Missouri has uniquely trained men, and those talents can be put to use in this format as well—to sharpen each other and teach the laity more, because so many in the pews are only getting Sunday morning.

Anecdotally, Bible study attendance seems to have dropped dramatically. The number of kids attending Sunday school has fallen. It’s like: “Let’s get to the service so we can get home for the Packers game.” That’s the cultural thing you’re talking about—what we’ve prioritized.

Football is a first-article gift. Don’t talk about it from the pulpit. You’ve got plenty of time to talk football. Don’t crack jokes about it. Just preach God’s Word. Football will take care of itself because it’s a multi–tens-of-billions dollar industry. It does not need your help, enthusiasm, or love.

The encouragement to pastors is: you have a limited window to deliver the truth that causes stony hearts to soften. The time must be focused on that. The effort must go into managing your words—every word is precious, whether it’s a ten-minute sermon or a forty-minute sermon. It’s no time to goof around.

Overall, it’s a sharpening of preaching skills. Dr. Koontz has done great work on how “goal–malady–means” preaching took over and became formulaic—switching to the five-fold use as another alternative.

And that’s why I’m blackpilled on the lectionary. The U.S. Constitution is for a people that can keep it. The lectionary is for a people incredibly well-versed in the Bible. You cannot do three readings a week that are siloed and expect most people in the pew to understand what’s going on—even within one sermon, never mind week to week.

Do a test in Bible study: ask who remembers the key points from your sermon. I’ll be surprised if even three out of a hundred can give you a meaningful recitation.

HOST: Hey, David—you were at my church on Sunday. What did I preach on?

DAVID: You preached about how love is knowledge, assent, and trust. Faith is… faith is a catch. That’s what it is.

HOST: Oh—hey. Did you remember that?

DAVID: Yeah.

HOST: You’re an ideal member. I always ask my kids at dinner after church: what was the sermon about? And they stare at me like cows staring at a new gate. But I think that’s because they’re so accustomed to hearing my voice—that’s my excuse.

WOOD: Yeah. But it goes to the point: we can’t criticize the laity for not reading their Bibles enough because we haven’t taught them how to read and comprehend.

In the same way, we need to teach congregations how to listen to a sermon. There’s a technique to it. There are cues people should listen for. They should come having pre-read the readings for the day, understand how they connect to the Gospel, and then listen for their pastor to take it out, explain it, and give the gift in that Word.

We’ve decided: “Well, the schools did a good enough job, so of course everyone comprehends speech.” That’s not true.

HOST: I’m finding with my confirmation kids that part of my primary task is teaching them how to read and comprehend

WOOD: Our lives have been subsumed in media. When speaking is done, it’s in a movie. They’re surrounded with pictures, symbols, story arcs. How does a kid on an iPad all day come to grips with a man standing and just talking? That’s unusual in our world.

And it’s different to hear a politician delivering a plank speech at a convention versus hearing a pastor speaking from God’s Word. That disconnect has grown.

Also: don’t do movie reviews. Pastors, run away from movie reviews. Don’t do popular culture. Throw away Star Wars references. The people have plenty of catechesis in mass media. You’re not connecting with youth by talking about the latest cartoon.

HOST: Well noted. And there’s too much stuff now—no monoculture. I have no idea what the latest Netflix thing is. You ever watched K-pop Demon Hunters? Apparently that’s overtaking the world.

WOOD: No!

HOST: Okay—yeah. I was expecting you to say yes.

WOOD: The title alone would have me running away. I’m very afraid of that other side of the invisible life. I don’t mess with it—not even playfully—because it is real.

And it’s another example of how surprised I am that Missourians don’t seem to believe demon oppression and possession exist today. It’s there. It’s clear. It’s only going to end when Jesus has blood flowing up to the bridles of the horses.

Until then, we need to step carefully in anything that interferes with that spiritual reality, including our problem with alcohol in the synod—our light attitude toward alcohol, which adjusts consciousness and makes intrusions possible.

HOST: Yeah. A man without self-control is like a city without walls, and you invite it when you break down your defenses, right?

WOOD: Right.

HOST: Great. That’s the law talking, right? The law.

WOOD: Right!

HOST: As you’re giving all of this really good advice to preachers, I’m like: “Would you just tell me it’s all forgiven and it’s okay?” Because you’re cutting me to the core.

But it’s really good. On my to-do list is: break down preaching into skills and make sure I’m honing them regularly—because the flesh is lazy. It’s easy to get comfy and cozy and lazy. We ought to be doing better all the time.

WOOD: Pastors are in an unprecedented era where the culture, through mass media, has catechized their people. Something radically different is needed.

I’m not talking about light shows and smoke machines. But the approach to preaching needs some sort of makeover because people are no longer able—even before trained—to hear what’s coming out of the pastor’s mouth. There’s a disconnect between how they receive speech in daily life and how they receive it in church.

The church is an island in the form of consumption. We shouldn’t be blasé and pretend it won’t have an effect.

HOST: Yeah, absolutely. Well, hey—I think I could talk to you for another couple hours. We’ll have to have you back on. That would be fun again.

But we really appreciate your time, Tim. God’s blessings to you and everything you do.

WOOD: Thanks, pastors. I appreciate the invitation. I appreciate the work you do for the church. Don’t lose hope. Don’t lose heart. Jesus will win. That’s written in that strange book at the back of the Bible.

We should look forward to it—and have an absolute desire that everyone else should look forward to it—with absolute confidence that I know where I’m going when it’s all done.

HOST: Amen. That’s a good note to end on.